|

||||

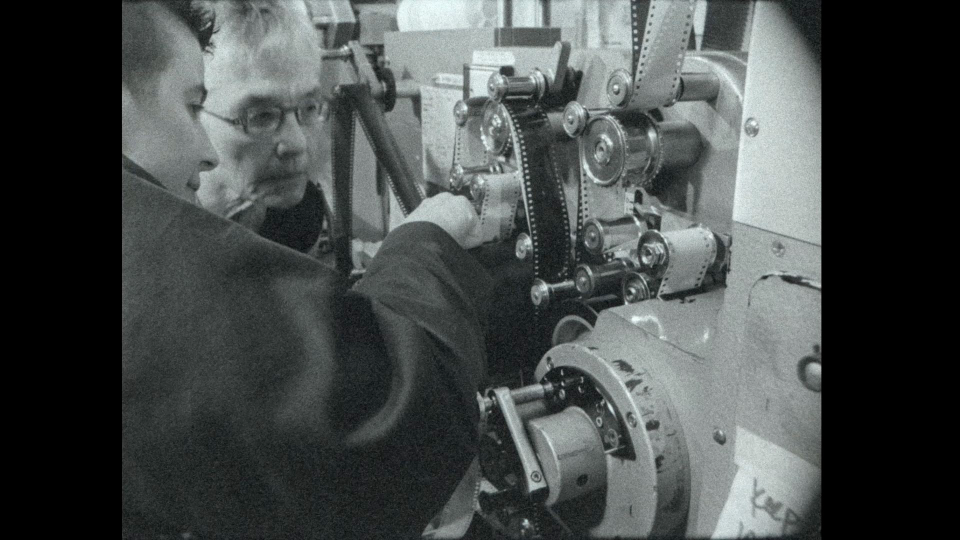

Still from Generations. (dir. Barbara Hammer and Gina Carducci, 2010). Used with permission from Gina Carducci. |

||||

Journal Issue 2.supplement

Summer 2010

Edited by Deanna Utroske, Agatha Beins, Karen Alexander, Julie Ann Salthouse, and Jillian Hernandez

Managing Editor: Katherine O’Connor

Generations: A Feminist Film as a Feminist Classroom

Essay by Gina Carducci

In art school I had to dig for information about Barbara Hammer and her generation of feminist experimental filmmakers; where were they? A few years later, it’s the beginning of another hot summer in New York, and I find Hammer is at my workplace for a screening. I introduce myself. I give her a tour of the film lab and the darkroom where I’m contact printing.1 I’m one of two women working with thirty men. This impresses her. We don’t hide our feminism or our queerness. This connects us. We are both filmmakers, but she’s been making films for forty years and I haven’t made a film since I finished art school five years ago. I show her my first film and she says we should make a film together about youth, age, and queerness. First ideas come from her; then our ideas come together.

A feminist collaboration breaks down hierarchy; so we do. How will we exaggerate age? She’ll circle the brown spots on her face. I suggest using a grease pencil that is used to mark film for editing, and I’m already picturing these circles alongside circular imperfections on the hand-processed film emulsion itself. What about our location? The beach, I suggest, because of her sunspots. Coney Island! The film reel is like the Wonder Wheel! We speak about the end of Astroland; we don’t speak about the end of film. We bring the literal and the metaphorical together. She suggests we call our film Generations. I like the way it refers to the generations of the filmmaking process. (Film shot in a camera is processed, printed, and possibly becomes an experiment in printing and reprinting. The process itself creates something new from the original image with each generation.)

We bring two generations together in a way that is queer, as though it’s hard to say which of us is the elder. So our collaboration is not that of apprentice and teacher, or younger and older. We’re different. My tape-measured studio shots differ from Hammer’s fluid cinematography, her dancing in and out of focus with the camera. We’re working well together, but she wants to be sure my part in the filmmaking isn’t just an expression of admiration. She suggests we each make our own edits of the footage we both shot together. She doesn’t want to edit on the flatbed2 , anyway; I don’t want to work in video. The old dyke—as she says—scans frame by frame for a digital edit to record back out to film; the young dyke uses the old tape splicer on the flatbed. Our collaboration is less a matter of generational succession than some sort of queer feminist creation of our own that lets each of us contribute just as we want to, apart from hierarchies of experience and inexperience. We decide we won’t look at one another’s edits until they are each complete, until we splice them together one after the other to make one film.

Before watching our two generations of edits, we sit at the flatbed with Hammer’s laptop nearby, we put film cores on our thumbs like rings, and we wear them throughout the screening. It’s a joke, a playful gesture—like friendship bracelets. But it’s also not a joke; it’s a commitment to stay together after we screen our edits. The experimental process is more important to us than controlling the product. But we like what we see.

Just as we broke down generational hierarchy, our film breaks down the hierarchy of viewing. The passive experience of watching is disrupted when you hear Hammer say, “Let’s turn off our lights,” and the film goes dark. The room you’re watching it in goes dark too. It’s as if we’re all talking in the dark, right here, audience and filmmakers; it’s strange and secretive for a moment, and then the light returns. On the screen, you see shots of the equipment that’s making the film you’re watching. You see the camera shoot in your direction. You see the circular motion of printing machines spliced with circles of sunspots, a film reel, and the Wonder Wheel on the last day of Astroland. Here, lesbian processing3 acquires a double meaning, at least: from the audience, you watch the film being processed, and you also become a participant in the process, a maker of meaning, while watching the making of a film. And you even watch the making of a filmmaker, encouraged to continue making.

Gina Carducci (carducci@mindspring.com) is a contact printer by day and a filmmaker by night. That leaves no time for sleeping but lots of time for filmmaking. Carducci’s first film Stone Welcome Mat (2003) premiered at the Venice Film Festival. This year Carducci collaborated with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore on All That Sheltering Emptiness (2010), and with Barbara Hammer on Generations (2010), which premieres at MoMA on September 15, 2010. As always, all shot on the Bolex, hand-processed in the kitchen, and edited on the flatbed. Film is not dead. Visit www.ginacarducci.com.

2A flatbed is a film editing machine for sound and picture that resembles a desk with plates on either side of a small screen in the middle. Film sits flat on the plates and is threaded through rollers along the table that lead the workprint through a prism that projects the picture on the screen, and the magnetic film through a track head that projects the sound. Film can be cut and spliced on the table while viewing the raw footage.

Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved.