|

||||

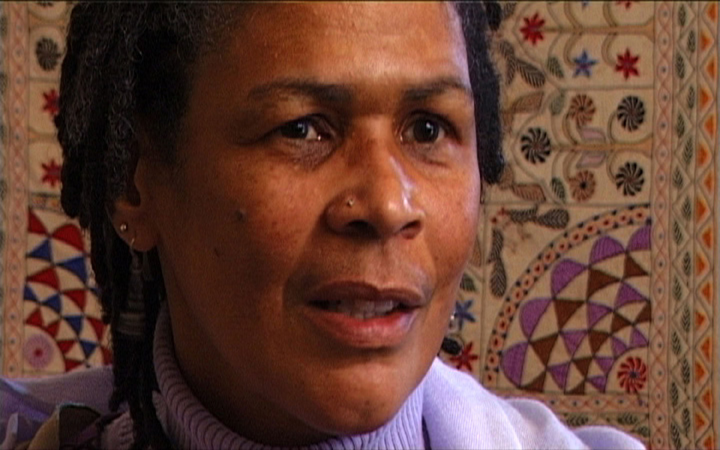

Still fromThe Noble Struggle of Amina Wadud. |

||||

Journal Issue 2.2

Fall 2010

Edited by Agatha Beins, Deanna Utroske, Julie Ann Salthouse, Jillian Hernandez, and

Karen Alexander

Editorial Assistant: Julie Chatzinoff

Conversations Across the Bosphorous. Directed by Jeanne C. Finley. New York: Women Make Movies, 1995.

Daughters of Wisdom. Directed by Bari Pearlman. Los Angeles: Seventh Art Releasing, 2007.

Living Goddess. Directed by Ishbel Whitaker. New York: Alive Mind Media, 2008.

The Noble Struggle of Amina Wadud. Directed by Elli Safari. New York: Women Make Movies, 2007.

Reviewed by Heidi E. Rademacher

Stories

of religion, faith, and spirituality have typically been narrated

through the experiences of men, despite evidence that women are

cross-culturally more religiously devout than men1 .

The four films reviewed here explore the diversity of ways in which

women understand, question, practice, and ultimately make meaning of

their faiths. Conversations Across the Bosphorous, Daughters of Wisdom,

Living Goddess, and The Noble Struggle of Amina Wadud each presents a

unique perspective regarding women’s relationships to faith and could be

effective tools for initiating discussion, complementing texts, and

analyzing the role of gender in a variety of religious settings.

Jeanne C. Finley’s Conversations Across the Bosphorous (42 min.)

documents two Muslim women’s different experiences growing up in

Istanbul. Finley couples poetic letters written by Mine Yashar Ternar,

reflecting on her secular upbringing, with the candid stories of Islamic

scholar Gokcen Hava Art’s orthodox childhood. Both women describe the

various struggles and challenges they face living in a city torn between

secular civil society and religiously conservative men and women. In

addition, Finley adds the reflections and opinions of scholars and women

of the community. These diverse voices paint an intricate and

compelling picture of a city and culture divided.

A

large portion of the documentary is spent discussing key issues related

to sexuality, gender, the body, and power, specifically the covering of

women’s bodies. Ternar romantically reminisces about her grandmother’s

simple headscarf worn for prayer. Art dismisses the effectiveness of

public covering by arguing that all women face harassment regardless of

attire. Other voices describe covering as a feminist act, a means of

control, a mechanism for separating public/male and private/female

spheres, an expression of modesty, a source of power for women, and a

symbol of women’s value.

As a tool for

initiating critical analysis in discussions of gender and religion in

the feminist classroom, Conversations Across the Bosphorous provides a

rich and diverse examination of Turkish women’s experiences with Islam

during the 1990s. While the film is limited in its examination of

religious practice, it could be an excellent work to pair with other

materials that examine Muslim women’s experiences in various cultures,

such as Elli Safari’s film The Noble Struggle of Amina Wadud (also

reviewed here) or the ethnographic studies of Lila Abu-Lughod2 .

Whereas Conversations

Across the Bosphorous focuses on scared tension in a secular

environment, Daughters of Wisdom (56 min.) is an exploration of life in a

homogeneous religious milieu. The highly engaging and beautifully shot

documentary highlights the voices of eight nuns of the Kala Rongo

Monastery in a remote northeastern region of Tibet. The film emphasizes

two key themes: the nuns’ experiences at and prior to coming to Kala

Rongo, and the role of the monastery in creating opportunities for women

to access education, authority positions and autonomy as well as change

traditional gender constraints.

The nuns

express numerous reasons for choosing a monastic life. Some seek to

remove themselves from the material world, while others fear suffering

and death. There are also those who express more practical reasons for

coming to Kala Rongo, such as gaining education, avoiding the dangers of

marriage and childbirth, or simply desiring freedom from the hardships

of rural Tibetan life. Each woman expresses extensive gratitude for the

opportunities presented by the monastery and the overall tone of the

film is highly celebratory of this unique spiritual institution.

However, nuns must still interact in a patriarchal system and struggle

with cultural doctrines that place more value on men and men’s

experiences. Even as eight nuns are selected for a new leadership

council, the idea that someday Kala Rongo might have a female abbot is a

concept that seems more utopian than realistic in the eyes of the nuns.

Daughters of Wisdom can also

help us explore important questions with regard to resistance, social

change, and patriarchy. However, the film provides the viewer with a

limited understanding of the Buddhist tradition as it is practiced at

Kala Rongo. With the exception of some focus on suffering and the

meditative practices of nuns staying in the retreat house, religious

practice is limited to transition shots and sound bites. Therefore,

Daughters of Wisdom would work best as either supplementary to

additional texts or in conversations that are not necessarily structured

around the religious tradition.

Ishbel Whitaker’s Living

Goddess (87 min.) presents the case of a rare and fascinating religious

tradition in Nepal, the living child goddess. The documentary focuses

on the life of one girl—eight-year-old Sajani—believed to be the

incarnation of the goddess Teleju as well as on the politically

motivated riots, demonstrations, and revolutionary violence that

occurred in Nepal in 2006.

The film

provides the viewer with an intimate look at the rituals of child

goddess worship from the perspective of the worshipped, as opposed to

the worshipper. While Sajani, the living goddess of the city of

Baktapur is the central figure in this documentary, the film also

highlights the lives of two other goddesses; Chanira, the goddess of the

city of Patan and Pretti the “Royal” goddess of Kathmandu. Each girl

has varying degrees of freedom and ritual duties. Goddesses are

expected to continue their ritualistic duties and obligations until

menstruation. After the onset of menstruation, it is believed Teleju

vacates the body of the living goddess. While former goddesses often

return to typical Nepalese life, the transition can be more difficult

for Royal Goddesses who are secluded from family and society throughout

their reigns.

Throughout the documentary,

conflict between students and Nepalese King Gyanendra’s army becomes

heightened, causing fear among the people and leading to questions about

the future of religion, specifically the worship of child deities. The

film climaxes with the king’s address in April 2006, when political

power is returned to the people. Protesters celebrate as the film cuts

to the goddess Sajani, not in her traditional makeup but in her school

uniform, leaving for school. She is almost unrecognizable among the

other students.

Living Goddess is an engaging

film that can serve as a strong pedagogical tool. While at times the

viewer might be unclear about specific individuals’ roles and

intentions, the majority of these discrepancies can be clarified on the

film’s Web site3 .

Complex gender relations are seen not only through religion, ritual,

and worship but also in the examination of the revolution and the recent

resignation of Sanjani from her position as a living goddess4 .

Although the length of the film might make it problematic for some

classrooms, scenes are constructed in a way that makes it easy for

instructors to play specific segments.

How does an

individual’s day-to-day life change when she challenges structures

within her religious tradition? This is the central question of Elli

Safari’s The Noble Struggle of Amina Wadud (29 min.). The short film

documents the life of a female African-American professor who led a

mixed-sex Islamic Friday prayer service in 2005.

The film focuses on the

beliefs and practices of Wadud and reactions to her statements and

actions. In coming to terms with her own faith Wadud has noticed

extensive injustice based on gender. Going straight to the Koran, she

has sought to find out if offenses against women were consistent with

holy text, and how to create a more balanced gender picture within

Islamic communities. While her actions have helped educate and empower

many Islamic women and men, they have also lead to threats and calls for

her resignation.

The compelling documentary

provides an excellent example of the intersections of race, gender,

politics, and religion. The film provides the viewer with a broader

understanding of the multifaceted and diverse interpretations of Islam

and with material for exciting analytical discussion and debate

regarding the fluidity and changing nature of religion, religious

practice, and the meaning of faith. In addition, the film outlines

motifs of resistance, empowerment, voice, and agency.

The films presented here all

cover various aspects of women’s relationships with faith, religion, and

spirituality. All four provide the feminist classroom with tools to

engage critical, analytical, and thought-provoking discussions around

themes of gender, power, resistance, and choice. In addition, the films

presented here stress the importance of examining women’s experiences

in the study of faith.

Heidi E. Rademacher is a graduate student in Brandeis

University’s joint Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies program. Her

academic interests include feminist theory, gender studies, sociology

of religion, and sociology of culture.

2Lila Abu-Lughod, Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in a Bedouin Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); Abu-Lughod, Writing Women’s Worlds: Bedouin Stories (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

4For more information on the resignation of Sajani Shakya, see http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7274132.stm.

Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved.