|

||||

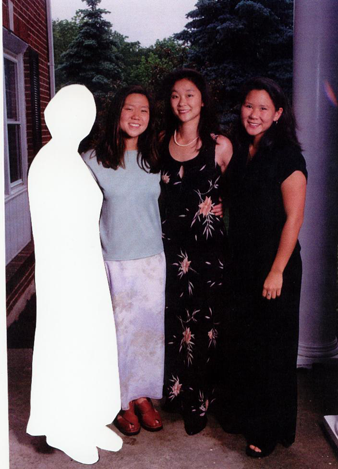

Still from Same Same, but Different. |

||||

Journal Issue 2.1

Spring 2010

Edited by Deanna Utroske, Julie Ann Salthouse, Jillian Hernandez, and

Karen Alexander

Editorial Assistant: Katherine O’Connor

37 Stories about Leaving Home. Directed by Shelly Silver. Berlin: Arsenal Experimental, 1996.

Between: Living in the Hyphen. Directed by Anne Marie Nakagawa. Montreal: National Film Board of Canada, 2005.

Same Same, but Different. Directed by Rosylyn Rhee. Venice, CA: Real Blonde, 2009.

Reviewed by Alexandra Hidalgo

In 37 Stories about Leaving Home,1 (52 min.) Shelly Silver interviews Japanese women about their relationships with other women in their families and about their own sense of self. Silver uses footage of life in Japan as well as stark black-and-white images of women’s underwear, wedding cake toppers, and music box ballerinas to illustrate what her subjects are saying. The beautifully crafted and haunting images, as well as the occasionally strident soundtrack, give the film an experimental edge that can help introduce students to divergent aesthetics and abstract modes of thinking through images. While the images don’t always literally reflect what is being said, they do fit the feelings conveyed by the women. Class discussion could center around Silver’s refusal to use traditional film styles to illustrate the lives of her female subjects.

Silver weaves a Japanese folktale into the film. An older woman narrates the tale and we see the faces of a mother and her daughter, who has been kidnapped by the monster Oni on her wedding day. As the interview subjects share their stories, we follow the mother as she strives to rescue her daughter. This folktale can be used to discuss how traditional narratives reflect and shape our understanding of society. Students may be asked to find similar stories in their own cultures and discuss in small groups how these stories have affected their own views of the world and of themselves.

The most powerful sequences in 37 Stories revolve around three generations of women talking about their families. Tamoko Hanawa, who runs a costume and bridal-gown rental business, describes her mother’s lifelong sacrifices, then says: “My ideal is to live my life like my father. I don’t want a life like my mother’s.” The film cuts to Tamoko’s daughter, who tells us: “My mother is not very family-oriented, so if I become a mother, I don’t want to be like her.” These scenes can be used to point out film’s ability to bring conflicting ideas together through editing in order to prove a point. The editing here demonstrates the complications of belonging to a family, and how, for example, a woman who desires to avoid becoming like her mother may end up becoming the person her own daughter longs avoid.

Between: Living in the Hyphen2 (43 min.) is Anne Marie Nakagawa’s exploration of what it’s like to be a racially mixed person in Canada. Nakagawa’s subjects explore their relationships to their different ethnicities and to their Canadian citizenship and recount the difficulties of reconciling who their bodies imply they are and who they really are. Interviewee Shannon Waters struggles with the fact that her First Nation heritage is hidden by her European features, while Fred Wah writes poetry to celebrate the Chinese genes barely visible in his Caucasian face. Karina Vernon, who is South Asian, Black, Russian, and German, describes being forcefully interrogated about her racial background by a bus driver. The subjects wrestle with the inability of their bodies to tell the complete story of their heritage, their struggle making the audience question to what extent physical appearances reflect actual backgrounds.

This struggle is especially present in the relationships between parents and children. For example, Tina Thomison, who is British and African American, but whose son looks Caucasian, recounts how once, when she was breastfeeding, a passerby remarked that Thomison must be babysitting because that couldn’t be her baby. Thomison, still shaken, explains, “It’s your child, the thing you love the most and someone’s telling you that it’s not even yours.” The mixed racial identities of the subjects make them vulnerable to the negation of the most basic of bonds, that between parent and child, making them face our culture’s privileging of the visual over other aspects of what constitutes a person.

In the classroom, students could be asked to evaluate how their bodies reveal their history and what assumptions they make about others based on appearances. The discussion could veer into the stronger emphasis placed on society’s control of female appearance and how racially mixed bodies complicate and undermine that control. Class discussion could also link women’s struggle to be valued beyond their visual appearance with the need by racially mixed people to have all aspects of their heritage validated, whether or not they’re visible.

Rosylyn Rhee’s Same Same, but Different3 (77 min.) is a more personal film than 37 Stories or Between. Also focused on parents and children, it is an autobiographical piece about Rhee’s relationship with her father. The fourth daughter of two Korean immigrants, Rhee, whose middle name, Sang Won, she translates as “No-More-Girl,” was the only one of her sisters to get into Harvard. However, when she decided to become a filmmaker instead of the lawyer her father dreamt she’d be, Rhee was kicked out of the family for two years. She received a grant from Harvard to make a documentary about her father’s return to Korea after a thirty-five-year absence, and father and daughter use the making of Same Same to reconcile. Students may be asked to explore the function of the camera in facilitating the rapprochement. How does the camera allow them to say to each other what they had never been able to communicate before? How would this film change if Dr. Rhee, not his daughter, were the filmmaker? Rhee’s work is a loving reversal of power relations, demonstrating the importance of having women not just in front of the camera, but behind it.

Rhee’s father, an affluent psychiatrist, describes their estrangement as a Cold War, and she uses the metaphor to link the relationship between the United States and Korea during the Korean War to her exclusion from her family. While her own Cold War started only after she declared her desire to be an artist, Rhee, who doesn’t speak Korean, has never been able to openly communicate with her father. Yet, in spite of their differences, Dr. Rhee managed to raise his children to attend Ivy League schools and succeed professionally. He explains that although he wanted a son, he decided to give his daughters a “better education than I can give my boys.” Aware of the advantages that males encounter in school and the workplace, Dr. Rhee decided to make it impossible for his daughters to fail, at the cost of the closeness they might have had. Instructors may use Dr. Rhee’s choices to explore the ethical dilemmas parents encounter when balancing a nurturing home and a successful education. They may examine the pressures that young girls—especially girls of color— undergo, not only to look a certain way (we see footage of the Rhee sisters competing in beauty pageants) but to outperform their male peers if they want to be competitive in the job market.

Together, the three films reviewed here can be used in a series to explore race, immigration, and parenting. Instructors could look to texts such as Children of Immigration and Lives Together/Worlds Apart, which also address the issues most prevalent in the films.4

Alexandra Hidalgo is a PhD student of Rhetoric and Composition at Purdue University, where she teaches film and English composition. Her scholarly research is focused on gender, race, immigration, and film. She is also a documentary filmmaker, currently working on a project about immigrant women in New York City.

Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved.