|

||||

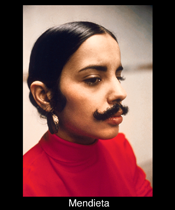

| Still from !Women Art Revolution (Lynn Hershman Leeson, 2010). Used with permission from Lynn Hershman Leeson. | ||||

|

||||

Journal Issue 3.2

Fall 2011

Edited by Julie Ann Salthouse, Jillian Hernandez, Agatha Beins, Karen Alexander and Deanna Utroske

Editorial Assistants: A.J. Barks and Anna Zailik

!Women Art Revolution. Directed by Lynn Hershman Leeson. New York: Zeitgeist Films, 2010.

Reviewed by Margo Hobbs Thompson

Lynn Hershman Leeson's !Women Art Revolution presents a comprehensive overview of the feminist art movement in the United States, from its inception in the late 1960s to the mid-2000s. Its content parallels the 2006 museum retrospective WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution and the standard text on the women's art movement The Power of Feminist Art1 ; for educators, this would make an excellent introduction to the feminist art movement in an upper-level class. Leeson self-consciously works against the "eradication" and "omission" of women artists from art history, and presents a first-person "secret history" comprising interviews with almost all the major players in feminist art from the past forty years--some represented in several conversations-- including artists Judy Chicago, Howardena Pindell, Yvonne Rainer, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, the Guerilla Girls, and Janine Antoni; art critic Lucy R. Lippard; and curators Marcia Tucker, Lowery S. Sims, and Connie Butler.

The film connects feminist art with the radical politics of the 1960s and 1970s: early on, a montage of the Black Panthers, the Berkeley Free Speech Movement (Leeson was a student there at the time), and the protest at the 1968 Miss America pageant staged by the New York feminist group Redstockings suggests that they were simultaneous and equivalent efforts. Later, stills of anti-Vietnam War demonstrations, students shot at Kent State, and the United Farm Workers support Leeson's argument that the prevailing trend in avant-garde art, Minimalism, was too rarefied in the face of the era's social and political protests. Feminist artists sought to change the institutional structure that upheld the vilified Establishment, and they demonstrated for equal representation with men at the Whitney Museum, the Corcoran Gallery, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Leeson productively extends this parallel between art and politics into the 1990s, when Anita Hill's testimony that Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her went unheard, and women responded by forming the Women's Action Coalition. In 1992, the Women's Action Coalition protested the Guggenheim SoHo opening exhibition for including only one woman: one has to ask, and Leeson attempts to answer, why had so little changed after almost twenty-five years of feminist art and activism?

Without laying blame, Leeson's film does not shy away from raising issues that have divided feminists. Curator and founder of the Franklin Furnace Martha Wilson reports that Judy Chicago shouted her down when she ventured that the look of the art produced at Chicago's Feminist Art Program (FAP) seemed somewhat prescribed. Chicago next appears on film berating an audience of women for rejecting political theory as "too hard" (the clip is from Joanna Demetrakas's The Making of the Dinner Party). African American artists Howardena Pindell and Adrian Piper discuss the race-consciousness that infused their work, and Cuban-born Ana Mendieta receives credit for curating an exhibition of non-white women at the New York women's cooperative gallery A.I.R. Lesbian artist Harmony Hammond recalls editing the "Lesbian Art and Artists" issue of Heresies in 1977, and the difficulty she had convincing lesbians to participate. The reason, she said, was that lesbian separatists at the time judged art making as "bourgeois." While Pindell, Piper, and Hammond make important points, the way the film frames them diminishes the very real and strong tensions between women of color and white women as well as between lesbian and straight women. Hammond, for example, has elsewhere observed that coming out as a lesbian could be career suicide for an artist, and Piper has expressed her alienation from white feminist artists and critics.2

!Women Art Revolution's treatment of the feminist generational divide is more nuanced. Young artists who came of age in the 1990s--Miranda July, Janine Antoni, and Camille Utterback (the latter two recipients of the MacArthur "genius" Award)--report that there was no readily available information on women artists active in the 1970s and their feminist studio faculty relayed an oral "secret history" to compensate. A "transgenerational haunting" marks their work: they recapitulated earlier feminist themes such as the mediation of femininity in Antoni's performance Loving Care (1992) which would have fit right in at the FAP's Womanhouse in 1972. It is poignant, once more, to hear that women artists are still overlooked even in top-notch art school curricula.

Leeson's film omits reference to the contestation of 1970s feminism's supposed essentialism that preoccupied academic feminists in the 1980s and 1990s; it is also silent on the issue of central core or vaginal imagery that supported the essentialism charge (Faith Wilding's Cunt Pillow from the FAP is shown briefly and unremarked). Leeson's evident preference for art politics over critical theory debates may be the reason that the "theoretical girls" of the 1980s--Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, and Barbara Kruger--are all but overlooked. Instead, the film punctuates the transition from 1970s to 1980s by noting the failure of the Equal Rights Amendment, Ronald Reagan's election, and John Lennon's murder. The new social and political landscape was negotiated by the Guerilla Girls with pointed humor; they rejected the "earnestness" of the 1970s as ineffectual.

Two trenchant critiques of the feminist art movement illuminate why women have not made more sustained progress in art institutions, markets, and canons. Art historian Amelia Jones observes that even today, the established structures of art production, exhibition, and reception are unchanged: women sought to be included in the art economy as it already existed. Artist Sheila Levrant de Bretteville implicates social class in the failure to effect real change: women artists, she said, were more concerned with persuading the patriarchy to share power and money with them as fellow members of the middle class. It would have been more revolutionary if they had realized that they were powerless and impoverished, and allied themselves with other poor and marginalized groups. Yet younger feminist artists remain hopeful: toward the end, Janine Antoni remarks, "We still have a lot of work to do."

!Women Art Revolution is all about using information to combat omission, and to that end, documentation is meticulous. The end credits identify all the talking heads, video clips, and slides. There is a website at Stanford where all the interviews (12,428 minutes worth) can be found.3 Another site, "Revolution Art Women" invites women artists to upload their work, to create a wiki-history of women's art.4 Both will be useful for educators.

1 Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, eds., The Power of Feminist Art (New York: Abrams, 1994).

2 Harmony Hammond, "A Space of Infinite and Pleasurable Possibilities," in Joanna Frueh, Cassandra L. Langer, and Arlene Raven, eds., New Feminist Criticism: Art Identity Action (New York: HarperCollins, 1994), 104; Adrian Piper, "Adrian Piper," Artforum 42, no. 2 (October 2003), 148; Adrian Piper, "Passing for White, Passing for Black," Transition, no. 58 (1992), 23.

Copyright © 2008. All rights reserved.