|

||||

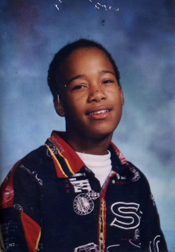

| Still from Dreams Deferred: The Sakia Gunn Film Project (Charles B. Brack, 2008). Used with permission from Third World Newsreel. | ||||

|

||||

Journal Issue 3.1

Spring 2011

Edited by Agatha Beins, Deanna Utroske, Julie Ann Salthouse, Jillian Hernandez, and

Karen Alexander

Editorial Assistants: Mimi Zander and A.J. Barks

Dreams Deferred: The Sakia Gunn Film Project. Directed by Charles Brack. Malibu, CA: Providence Productions, 2008.

Trained in the Ways of Men. Directed by Shelly Prevost. Fremont, CA: Reel Freedom Films, 2007.

Reviewed by Reese C. Kelly

Charles Brack’s Dreams Deferred and Shelly Prevost’s Trained in the Ways of Men examine the murders of gender nonconforming teenagers: a fifteen-year-old African American aggressive1 named Sakia Gunn and a seventeen-year-old Latina trans2 woman named Gwen Araujo, respectively. Featuring footage of the criminal trials, community activism, and interviews with community members and educators, both documentaries prompt student discussion on various issues including masculinity, heterosexism, racism, and cissexism.3 In each film, the absence of a narrator creates an intimacy through which one can bear witness to these crimes, compelling the viewers to empathize with the subjects. However, without a clear narrative trajectory, both films appear disjointed, with seemingly unrelated scenes and interviews weakening their overall educational effectiveness.

Dreams Deferred opens with the question, “Who was Sakia Gunn?” Following this with many “I don’t know” responses, Brack highlights the lack of media attention paid to Gunn’s story. Gunn, an aggressive, moved through the world being perceived by some as a young heterosexual man and by others as a masculine lesbian. On the night of her murder, Gunn and her friends were waiting at a bus stop. Two men pulled over to flirt with and proposition the femmes in her group, but when their advances were rebuffed by the girls’ declaration of their lesbianism, the men attacked and Gunn was stabbed to death. Whether it was Gunn’s female masculinity, the discovery that the femme’s male-appearing mate was a woman, or the young girls’ unavailable sexuality, each one of these possible scenarios represents a threat to black masculinity, characterized by hyper-heterosexuality, hyper-masculinity, and the control over black female bodies.4 Gunn’s social location as a young, African-American, working-class, gender nonconforming female marks her as dispensable to society and her death as inconsequential to the mainstream news media. Within the first month of her murder, Gunn’s story appeared in the news only eight times as opposed to the four hundred and forty-nine reports on the murder of Matthew Shepard, a “well-to-do, white boy-next-door who happened to be gay.”5 Alternative news outlets remained silent as well, reflecting multiple issues to which Dreams Deferred calls attention: racism and classism within some LGBT communities, the denial of queer sexualities by some people in African-American communities, and the reluctance of some people in black communities to discuss black male violence against black women and children.6 These issues reflect systemic problems that are a result of institutionalized racism, sexism, and heterosexism and do not reflect the beliefs and actions of all, or even most, African Americans.

The murder of Gwen Araujo is another illustration of how violence is used to mark individuals as “other” and less than human. Araujo was brutally beaten and murdered by a group of individuals including lovers and friends, arguably when it was “discovered” that she was trans. Like Brack, Prevost analyzes news reports of Araujo’s murder to show how the continued use of Araujo’s birth name and assigned sex reinforce the dehumanization and invalidation of transpeople. Unfortunately, in Trained in the Ways of Men Prevost perpetuates a similar type of identity invalidation through the unnecessary use of video footage and photos of Gwen as a young boy. In her attempt to reconstruct Araujo’s life to fit within a hegemonic transsexual narrative7 and with her focus on heterosexism rather than cissexism, Prevost missed an opportunity to address an element at the heart of gender policing – deception. As Julia Serano states,

“Deception” is the scarlet letter that trannies are made to wear so that everybody else can claim innocence. This is why the police, lawyers, and press who worked on the Gwen Araujo case ignored the multiple sources who insisted that Gwen’s killers knew she was transgender to begin with. It’s why nobody ever questions how next-to-impossible it would be for two of Gwen’s killers to have had anal sex with her without ever coming across her genitals. Nobody was willing to even consider the possibility that Gwen’s murderers knowingly had sex with her.8

Both murders provide a clear illustration of how violence against women, lesbians, and trans people is used to bolster and sustain hegemonic masculinity. In teaching both of the films reviewed here, educators could consider using Transgender History by Susan Stryker; Invisible Lives by Viviane Namaste; Trans/Forming Feminisms edited by Krista Scott-Dixon; Transgender Rights edited by Paisley Currah, Richard Juang, and Shannon Price Minter; and Nobody Passes edited by Mattilda, a.k.a Matt Bernstein Sycamore.9 Overall, Dreams Deferred provides a more sophisticated analysis than Trained in the Ways of Men, which lacks more information than it offers. Furthermore, the take-away message from Dreams Deferred is to empower queer youth of color and to hold communities responsible for addressing diversity and inequalities, whereas Trained in the Ways of Men calls for hate crime legislation, which reinforces the authority of a racist and classist legal system.

Reese C. Kelly is a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University at Albany, State University of New York, where he is writing his dissertation on the ways in which trans people negotiate their identities across various identity checkpoints. Currently, he holds the position of Visiting Lecturer in Women’s & Gender Studies and Sociology at the University of Vermont.

1 Aggressive is slang terminology referring to masculine identified lesbians (and some trans men), usually within urban black queer communities.

2 Trans is used to describe individuals who have moved away from their sex assigned at birth. Conversely, cis is used to describe individuals who identify with their sex assigned at birth.

3 The words heterosexism and cissexism replace the commonly used terminology of homophobia and transphobia to emphasize the fact that inequality is not just bias or fear, but a systematic and institutionalized set of attitudes, beliefs and practices. Cissexism refers to attitudes, beliefs and practices that trans people’s genders are inferior to or less authentic than those of cis people.

4 Patricia Hill-Collins, Black Sexual Politics (New York: Routledge, 2004), 174.

5 Kim Pearson, “Small Murders: Rethinking News Coverage of Hate Crimes Against GLBT People,” in News and Sexuality: Media Portraits of Diversity, eds. Laura Castaneda and Shannon Campbell (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2006), 159-190.

6 Mark Anthony Neal, “Baby-Girl Drama: Remembering Sakia,” PopMatters, January 27, 2004, http://www.popmatters.com/features/040127-sakiagunn.shtml.

7 Sandy Stone, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto,” in The Transgender Studies Reader, eds. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle (New York: Routledge, 2006), 221-235.

8 Julia Serano, Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity (Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2007), 248.

9 Susan Stryker, Transgender History (Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2008); Viviane Namaste, Invisible Lives: The Erasure of Transsexual and Transgendered People (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000); Krista Scott-Dixon, ed., Trans/Forming Feminisms: Transfeminist Voices Speak Out (Toronto: Sumach Press, 2007); Paisley Currah, Richard M. Juang, and Shannon Price Minter, eds., Transgender Rights (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006); Mattilda a.k.a. Matt Bernstein Sycamore, ed., Nobody Passes: Rejecting the Rules of Gender and Conformity (Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2006).

Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved.