|

||||

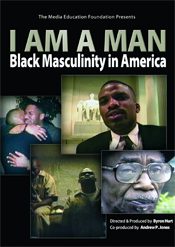

| Still from I Am a Man: Black Masculinity in America (dir. Bryon Hurt, date 1998). Used with permission from Media Education Foundation. | ||||

|

||||

Journal Issue 3.1

Spring 2011

Edited by Agatha Beins, Deanna Utroske, Julie Ann Salthouse, Jillian Hernandez, and

Karen Alexander

Editorial Assistants: Mimi Zander and A.J. Barks

Michael Kimmel on Gender: Mars, Venus or Planet Earth? Men & Women in a New Millennium. Directed by Sut Jhally. Northampton, MA: Media Education Foundation, 2008.

I Am a Man: Black Masculinity in America. Directed by Byron Hurt. Northampton, MA: Media Education Foundation, 1998.

The Smell of Burning Ants. Directed by Jay Rosenblatt. Harriman, NY: Locomotion Films, 1994.

Reviewed by Jørgen Lorentzen

The films reviewed here are three very different portrayals of men and masculinities when it comes to both content and cinematic style. Let me start with undoubtedly the best of these three films, the screening of Michael Kimmel’s lecture (54 min.) at Middlebury College in Vermont. Kimmel is one of the most renowned and respected researchers on men and masculinities in the world, and he has written and edited many books in the area. One of his best known is an alternative history of America, Manhood in America: A Cultural History (1996).1 Kimmel has traveled widely as a speaker and lectured for students, professionals, and politicians in classrooms, in public spaces, and at conferences all over America. He has acquired a style and competence in performing for larger audiences, which is clearly visible in this documentary film. Kimmel is able to unite ethos, pathos, and logos in a refined way. The combination of self-confidence and rhetorical precision makes the film very useful for the classroom. Even though the film is the opposite of television in many ways—no action, no drama, only one camera and Kimmel himself—the combination of the performance and the topics Kimmel talks about—gender and sexuality—makes it an exciting hour to watch.

In the lecture Kimmel goes through the most important areas of gender equality research and politics: education, work place, family, violence, and sexuality. One of Kimmel’s great advantages is that he is able to provide a perspective on both women and men, including both genders in his flowing discourse on the difficulties and progress regarding gender equality. His opening remarks give a good picture of this, particularly when he states that he differs from John Gray’s idea about men being from Mars and women from Venus in that our similarities when it comes to traits, attitudes, and behavior actually outweigh our differences.2

I Am a Man: Black Masculinity in America (60 min.) is former quarterback Byron Hurt’s search for who he is as a black man in contemporary America, or as he puts it: “How I cope with being black and male in America.” To answer that question, he journeys across the country, speaking to men young and old and to different spokespersons from the black community, such as the cultural critics bell hooks and Michael Eric Dyson, author Kevin Powell, historian John Henrik Clarke, former mayor of Atlanta Andrew Young, and rap artist MC Hammer. As a narrator, he guides us through his journey into seven different areas of thought on black masculinity: coolness, emotions, homosexuality, violence and fears, sexism, fatherhood, and the future. The philosophy of the film is based on a constructivist perspective, namely that human beings are all born with creativity, love, trust, openness, curiosity, courage, leadership, and so on; it is what happens after we are born that changes us. For males in the United States, masculinity has to be earned. It is something you have to gain, sometimes even fight to get, and sometimes you may think that it is guns, girls, and drugs that give you that masculinity.

Through the film we begin to understand that masculinity often is created by not doing or not showing. Coolness gives you respect by being like ice, for emotions are not to be talked about, homosexuality is not to be seen, and speaking about sexism, violence, and fears is taboo. In this stereotypical cultural image black masculinity is a lack of language, a suppression of oneself, and a splitting from the inner self. bell hooks states in the film that “within a white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy, black men can’t begin to liberate themselves without interrogating and questioning how sexism has shaped the nature of black masculinity,”and, I would add, without interrogating and talking about black masculinity at all. And this is what Byron Hurt does in this film. It is not by accident that the segment on fatherhood is right before a segment on the future. Fathering and a better future are closely connected in Hurt’s film, and as he says, if fathers would be present and express love for their kids, we would see an immense change mentally, spiritually, physically, and emotionally in the life of the whole family.

The Smell of Burning Ants (21 min.) is written, directed, and edited by the San Francisco– based independent filmmaker Jay Rosenblatt. The film has already achieved its own history during the sixteen years since it was originally made, having been screened in film festivals all over the world and received many different prizes. It is also worth mentioning that at Rosenblatt’s website there is a study and discussion guide for the film (http://www.jayrosenblattfilms.com/smell_of_burning_ants.php), both of which give ideas for using the film in classroom work. Since the film has a psychological and deep emotional temperament it is important to spend time discussing and processing it.

In general, the film has a philosophy based on the much simpler language of boyhood socialization: what others do to you, you do to others. When you experience violence or anger you become angry and use violence yourself. Masculinity is thus also a reflection of continuous competition in the male world, harassment, and violence. It is also about how this anger is directed toward other boys, toward girls and, in the cases presented in the film, also toward all sorts of animals: ants, flies, worms, slugs, beetles, rats, turtles, cats, rabbits. These are all possible objects of torture for angry boys. Burning ants is a favorite specialty. One of the most important messages in the film is that boyhood socialization is about not knowing. The boys seldom know why they are punished, why they are being hurt from the day they are born, or why they are told not to do this or that. The combination of this void and the continuous filling up of it with all kinds of violence makes boys simultaneously vulnerable and dangerous.

Even though the film has many useful qualities, I am hesitating. The reason for this is perhaps the dramatic language that seems a little bit outdated and makes it less valuable today. The black and white art-movie impression has a feeling of being antique and therefore creates a distance that may be too hard to overcome in the classroom. The same holds for the insistent voice-over (by Richard Silberg), which is so dramatic that it could be hard for youngsters to follow in the classroom.

Jørgen Lorentzen (j.l.lorentzen@stk.uio.no) is a Professor at the Center for Gender Research at the University of Oslo. He has written several books and articles within the field of cultural studies, literary analysis, and masculinities, the most recent of which are Män i Norden: Manlighet och modernitet 1840-1940, edited with Claes Ekenstam (Nordic men: Manliness and modernity 1840-1940; Hedemora: Gidlunds, 2006), Kjønnsforskning. En grunnbok, edited with Wencke Mühleisen (Gender studies: An introduction; Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2006), and Maskulinitet (Masculinity; Oslo: Spartacus, 2004). He has been the leader of the research project Men and Masculinities at the center and is now leading a new project with Wencke Mühleisen on intimacy called Being Together.

Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved.