|

||||

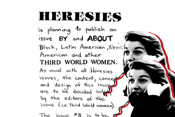

| Still from The Heretics (dir. Joan Braderman, 2009). Used with permission from the Heresies Film Project. | ||||

|

||||

Journal Issue 3.1

Spring 2011

Edited by Agatha Beins, Deanna Utroske, Julie Ann Salthouse, Jillian Hernandez, and

Karen Alexander

Editorial Assistants: Mimi Zander and A.J. Barks

Judy Chicago and the California Girls. Directed by Judith Dancoff. Los Angeles: California Girls Productions, 1971/2009.

The Heretics. Directed by Joan Braderman. New York: Crescent Diamond/Heresies Film Project, 2009.

Guerrillas in Our Midst. Directed by Amy Harrison. New York: Women Make Movies, 1992.

Reviewed by Jennie Klein

Was there a feminist revolution in art? Thirty-plus years after second wave feminism collided with the art world and forced it to confront engrained prejudices and stereotypes about artists who were not white, male, and heterosexual, it is easy to forget how closed off the art world was to anyone who was not white, middle class, and male. All that changed in the seventies. Feminist artists refused to go about business as usual, choosing instead to establish programs for teaching women; to put together a magazine about art, revolution, and feminism; and to expose the male-biased capitalist underpinnings of the New York art world. As the feminist art historian Arlene Raven stated in an interview that took place shortly before her death, “We truly thought we were changing the world in 1970, and I think that I have learned a great deal about what it takes to change the world and what kind of power you have to have, at what level you have to be.”1

The three films discussed here are about the women who changed the art world and our world in the seventies. In 1970, Judy Chicago, who is best known for her monumental feminist installation The Dinner Party (1980) and her theorization of central core imagery in feminist art, set up a unique program for women students at Fresno State College. Called the Feminist Art Program (FAP), Chicago ran it for one year in Fresno, after which she—along with nine of her students—transferred to the California Institute of the Arts. The earliest of these three films, Judy Chicago and the California Girls (running time 27 minutes) focuses on Chicago and her first class of feminist artists. Directed by Judy Dancoff, the film, which was made in 1971 but finished in 2009, includes footage of Chicago’s class rehearsing Cock Cunt Play, a role-playing performance piece written by Chicago; the Cunt cheerleaders welcoming Ti Grace Atkinson to California; and a heated debate between Chicago and Atkinson about the role of men in feminism. Filmed in black and white, Judy Chicago and the California Girls suggests that the project of educating future feminist artists was serious. For scholars who have studied the beginnings of the feminist art movement in Southern California, the film is a nice complement to the two films made by Johanna Demetrakas about this period of feminist art: Womanhouse (1974) and Right Out of History: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party (1980). Educators who wish to use this film should keep in mind that Chicago’s role as a feminist educator was brief—publications such as A Studio of Their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Experiment,2 a catalog that accompanied an exhibition of the same title, gives a more nuanced view of the early feminist movement that is less focused on Chicago.

The Heretics (running time 91 minutes), directed by Joan Braderman, is about the original members of the collective that produced the feminist art magazine Heresies, which ran from 1977 to 1993. From the start, Heresies was a unique publication, one that mixed Marxism, feminism, and art. Heresies was founded at about the same time as feminist publications such as Chrysalis, Signs, Feminist Studies, Frontiers, and Spare Rib (published in the UK), and it had much in common with these publications, which were initially geared toward an informed audience that was not necessarily academic. In keeping with the spirit of the original publication, which was designed to resemble the agitprop collage of artists such as Hannah Höch, Braderman shot the movie so that the scenes resemble pages from the magazine. Designed to be a microcosm of the second wave feminist movement, the film includes extensive interviews with twenty-four members of the original collective, including Lucy Lippard, Mary Beth Edelson, Ida Applebroog, Susana Torre, Harmony Hammond, and Cecilia Vicuña. Watching these interviews, one is struck by the commitment of these women, many of whom continued to embody their radical political vision both through their art making and their lives long after their time with the collective. Susana Torre’s career subsequent to her involvement with the Heresies Collective is indicative of the way in which the feminist politics of the collective influenced career choices. An architect, Torre returned to her native Spain and devoted her career to designing living quarters that were environmentally friendly and encouraged communal living. The Heretics is a particularly good choice for those educators interested in showing a film in conjunction with a discussion of second wave feminism in the art world because it doesn’t focus on just one artist or critic (unlike Judy Chicago and the California Girls) and because it is accompanied by an absolutely terrific website that includes PDFs of all of the issues of Heresies ever published.3

The third film included in this review, Guerrillas in Our Midst (running time 35 minutes), tells the story of the Guerrilla Girls, who formed in the mid-eighties to counter the increasingly careerist and still male-dominated art world. The Guerilla Girls got their start in 1985, when they protested An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, which included only 13 women. Calling themselves “girls” in order to reclaim the term in the same way that “queer” has been reclaimed, the Guerilla Girls hid behind gorilla masks and the names of famous women artists so that people would focus on the issues rather than on them and their work. The film, made in 1992, is very much in the spirit of early third wave feminism which was epitomized in the art world by the 1994 bi-coastal exhibition Bad Girls curated by Marcia Tucker and Marcia Tanner.4 Third wave feminism, unlike second wave feminism which was exemplified by Judy Chicago and her theories about central core imagery and a universal feminine identity, was much more concerned with exploring the way in which language and culture were inherently sexist. It also embraced the idea of the “bad girl”—a woman who was unapologetically “unfeminine” in her demeanor. Outspoken, radical, humorous, and media savvy, the Guerrilla Girls donned gorilla masks in order to mount stealth attacks on the art world. Under cover of the night, they put up posters all over New York City that challenged the gender and racial inequities that existed in the exhibition policies of major museums and galleries. They appeared on newscasts and panels to decry the insidious politics of the art world, which were hidden behind terms such as “genius” and “quality” and which served the pursuit of money.

Guerrillas in Our Midst is a short, humorous film that has held up well even though it was made almost a decade ago. The Guerrilla Girls posters, many of which are iconic, take center stage in this movie. For those educators wishing to teach third wave feminism, the Guerrilla Girls website (http://www.guerrillagirls.com/) which reproduces many of the posters, would be a helpful resource in conjunction with a discussion of this movie. It would also be helpful to show some of the videos and films included in Bad Girls Video, which Cheryl Dunye curated for Bad Girls. The history of feminist art is one that is multi-faceted and complex. These three films, when viewed together, encapsulate the differences between second wave feminism on the east and west coasts, and then suggest the direction taken by feminism in the 90s. I would recommend using these films in conjunction with a more nuanced reading of feminism and feminist art that takes into account issues not addressed in these films such as feminist art made in countries other than the United States, and feminist/queer theoretical treatments of representation/visual culture. Questions that are particularly relevant vis-à-vis these films include the relevance of Chicago’s pedagogical methods, the efficacy of the Marxist-feminist approach as exemplified by the Heresies Collective, and the continuing sexism (and sexist construction) of the art world. These films would be particularly interesting if taught with Lynn Hershman Leeson’s !Woman, Art, Revolution (2010), a documentary about the feminist art movement .

Jennie Klein is an associate professor of art history at Ohio University. She has published extensively on feminist art from the seventies and is presently working on a book project on feminism, the goddess, and feminist performance.

1Arlene Raven, “Looking Through a New Lens: Terry Wolverton Interviews Arlene Raven,” From Site To Vision: The Woman’s Building in Contemporary Art, Sondra Hale and Terry Wolverton, eds. (Los Angeles: The Woman’s Building, 2007), 120.

2Laura Meyer, ed., A Studio of Their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Experiment (Fresno: Press at California State University, 2009).

3The Heretics, http://helios.hampshire.edu/nomorenicegirls/heretics/#home.

4 See Marcia Tucker, ed., Bad Girls (Boston: MIT Press, 1994). There were two exhibitions: Bad Girls at the New Museum of Contemporary Art and Bad Girls West at the UCLA Wight Gallery.

Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved.