Trans of Color Histories, Visibility, and Violence in The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson

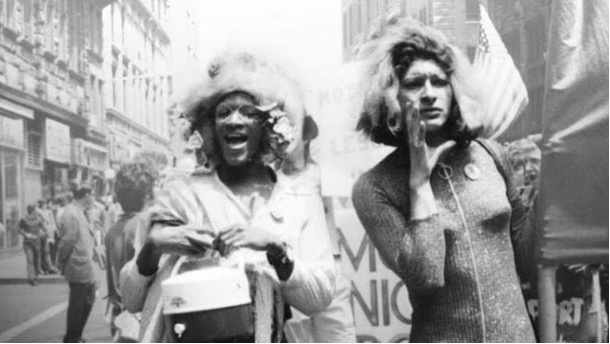

Fink, Leonard. “Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries at the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, 1973.” Photograph. 1973. Digital Transgender Archive, (accessed January 5, 2024). Published according to fair use policy.

In my upper-level seminar, Queer Media Studies, students investigate the history of LGBTQ+ representations in a range of US popular media since the 1950s, including television and film. The course’s focus is trifold: by considering sociocultural contexts we interrogate queer and trans aspects of media production, media reception, and the texts themselves. Students are thereby introduced to major debates and theoretical frameworks surrounding queer and trans media studies and critically analyze how sexuality and gender identity are always already intertwined with race, class, ability, nationality, and other lines of power in shaping LGBTQ+ culture and experiences. David France’s documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson (2017) presents a useful teaching tool for discussing specifically the erasure of queer and trans people of color’s contributions to LGBTQ+ history, the politics of trans visibility, and the violence that such visibility often engenders.

The film chronicles the life of Marsha P. Johnson and her best friend Sylvia Rivera, both trans women of color, and their—often overlooked—activism and contributions to the gay rights movement in New York City in the 1960s and 1970s (see also Ferguson 2019; Ryan 2017). The film follows Victoria Cruz, a trans activist elder from New York City’s Anti-Violence Project, and her investigation into Johnson’s death in 1992, which police initially ruled a suicide despite suspicious circumstances. Through Cruz’s advocacy and her quest to determine how Johnson really died, the viewer is confronted with links between the historic violence and erasure that trans women of color like Johnson and Rivera faced during their lifetimes and the epidemic of violence and neglect that continues to disproportionately impact trans communities of color today.

Lesson Plan

Students watch the documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson (available on Netflix) either together in class or at home. Accompanying the film are two academic chapters (Ferguson 2019; Saffin 2021) and two shorter popular press readings (Ryan 2017; Tourmaline 2017). To help frame an in-class discussion of the film, I contextualize and highlight three key themes with corresponding discussion questions.

Gay Rights for Whom? The Erasure of Johnson and Rivera from LGBTQ+ History

Discussion Questions

- Why have the contributions of Black and Latinx trans women like Johnson and Rivera been erased from LGBTQ+ history?

- What does the whitewashing of Stonewall’s origin story reveal about whose voices and histories are considered valuable and about gay rights as a single-issue politics?

- Despite the fact that Rivera’s story and interview segments comprise a significant portion of the film, she is completely erased from the title—what do you make of this?

- What are some current examples of the persisting schisms and tensions between gay and trans communities?

Through original archival footage that includes interviews with Johnson and Rivera, as well as some of their family members and acquaintances, the documentary illustrates how both were often treated as outcasts, not only by mainstream American society but by the gay rights movement itself. Johnson and Rivera thus recognized the need to create their own safe community spaces. They understood that poor, hustling street queens and “transvestites” (the term transgender did not exist back then), who are subject to intersecting oppressions, often face additional barriers, discrimination, and harassment, which relegate them to the margins of the marginalized. The documentary depicts this tension most powerfully by showing footage of Rivera’s now infamous “Y’all Better Quiet Down” speech at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day: “I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment for gay liberation and you all treat me this way? What the fuck’s wrong with you all? Think about that!” (38:37). An interview segment from the 1990s follows, showing Rivera carefully reflecting on the narrow and exclusionary confines of white-gay-middle-class acceptability, expressing that “the movement had completely betrayed the drag queens, the people on the street” (40:10).

Similarly, in his analysis of the multidimensional beginnings of gay liberation, Roderick Ferguson argues that Stonewall “was not simply about confining queer and trans liberation to the narrow parameters of single-issue politics, but about connecting that struggle to the network of insurrections that was developing all over the US, a network made-up of feminist, anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and anti-war movements” (2019, 19). In other words, Stonewall was not a spontaneous event that politicized previously apolitical trans of color subjects, as the now dominant mythical origin story likes to suggest; rather, it was informed and produced by various other protests and acts of civil disobedience happening throughout the country: “it is more accurate to say that trans women were the intersectional linchpins between anti-racist, queer, and transgender liberations” (Ferguson 2019, 21). Prior to Stonewall, both Johnson and Rivera had, for example, extensively participated in protests against Bellevue Hospital using electroshock therapy on queers and in sit-ins at New York University demanding open admission for minority students (see Ferguson 2019). As the film highlights, Johnson’s and Rivera’s intersectional understanding of liberation ultimately led to the founding of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970, a radical mutual aid project that provided housing, food, and health resources for queer and trans street kids and sex workers.

Who Gets To Tell Trans Stories? The Politics of Trans Visibility

Discussion Questions

- What does the controversy surrounding the production of the documentary, specifically Tourmaline’s accusations that France did not credit her work, reveal about media production, capitalism, and privilege?

- In terms of transgender storytelling, do you think it is important to have trans people themselves both behind the scenes and on screen?

- What changes in the industry can enable more trans people “to be the architects of our own narratives” (Tourmaline 2017)?

Shortly after the documentary’s release in October 2017, Black trans activist and artist Tourmaline (2017) accused director David France of “finding inspiration” for his movie from a grant application she and Sasha Wortzel had submitted for a short film project on Johnson (ultimately released as Happy Birthday, Marsha! in 2018) and of using archival footage without her permission or crediting her work.1 As a white, gay man with an extensive filmography, France, unlike Tourmaline, had access to Hollywood’s social and cultural capital to obtain funding for this project that allowed him (like many other white cis male authors, producers, directors, and actors) to tell, appropriate, and extract value from the stories of Black and Brown trans women without crediting or acknowledging Tourmaline for the years of unpaid labor she had spent digging through archives, libraries, and living rooms to digitize this previously inaccessible content. What Tourmaline’s experience illustrates are the insidious connections between the historic erasure of trans women of color from the LGBTQ+ movement in the 1960s and 1970s and the transphobic violence and disposability that continues to haunt many of them today. As Tourmaline (2017) notes, the “historical erasure of black trans life means so many of us are disconnected from the legacies of trans women before us, denied access to stories about ourselves, in our own voices.”

An Epidemic of Violence

Discussion Questions

- What connections does the film draw between Johnson’s unresolved death and the current epidemic of violence and discrimination targeting trans communities?

- Johnson and Rivera embodied an intersectional politics in their fight for a better world—advocating for prison abolition, housing, health care access, and the decriminalization of sex work to name a few. What do you think are key intersectional and coalitional issues for queer and trans movements today?

The documentary does not conclude with a “happy ending.” Despite Cruz’s best efforts—she uncovers gross police neglect in their investigation, including omission of crucial witness statements and missing case files—Johnson’s death remains unresolved. And in the film we see Rivera struggling with poverty, homelessness, and addiction throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. A particularly depressing segment shows a disheveled Rivera as her makeshift encampment at the Christopher Street Pier gets raided to make room for developers and gentrification: she speaks to the camera, “Yeah I am crazy because the world has made me crazy” (79:15). As such, the violence and neglect both Johnson and Rivera experienced during their lifetime exemplifies ongoing struggles of trans communities of color today, which the film highlights, for example, through activists demanding accountability in the case of Islan Nettles who was brutally beaten to death in Harlem in 2013. Fast forward to 2023 when more than thirty trans people, the majority of whom are Black and Latinx trans women, were murdered (Keller 2023), and the American Medical Association in 2019 officially declared the violence against trans communities to be an “epidemic” (Ennis 2019). Trans people disproportionately experience barriers to education, employment, housing, and health care, which makes them more likely to engage in underground economies for survival, and in turn puts them at a higher risk for experiencing violence (for sobering statistics, see James et al., 2016). As Croix Saffin importantly explains, “The disproportionate rates of violence committed against black, indigenous, and Latinx trans women/trans femmes are a result of systems of oppression—white supremacy, racism, cissexism, trans misogyny, and sexism—working concurrently. These systems of oppression impede access to social, economic/material, and emotional resources” (2021, 139).

Conclusion

As we are currently witnessing unprecedented legislative efforts to restrict trans people’s rights to play sports, use bathrooms, and/or receive gender-affirming health care, The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson allows educators and students to grapple with the complexities of LGBTQ+ history, the politics of trans visibility, and the violence targeting trans communities of color today. The film encourages us to ask how we can engage in queer and trans worldmaking that honors those trans elders who have already passed while protecting, valuing, and fighting for the trans and nonbinary lives among us.

Works Cited

The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson. 2017. Directed by David France. Los Gatos, CA: Netflix, 105 minutes.

Ennis, Dawn. 2019. “American Medical Association Responds to ‘Epidemic’ of Violence against Transgender Community.” Forbes, June 15.

Ferguson, Roderick A. 2019. “The Multidimensional Beginnings of Gay Liberation.” In One-Dimensional Queer, 18-45. London: Polity.

Happy Birthday, Marsha! 2018. Directed by Tourmaline and Sasha Wortzel. San Francisco: Frameline, 14 minutes.

James, Sandy E., Jody L. Herman, Susan Rankin, Mara Keisling, Lisa Mottet, and Ma’ayan Anafi. 2016. Executive Summary of the Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

Keller, Jarred. 2023. “HRC Foundation Report: Epidemic of Violence Continues; Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People Still Killed at Disproportionate Rates in 2023.” HRC Foundation, November 20.

Ryan, Hugh. 2017. “Power to the People: Exploring Marsha P. Johnson’s Queer Liberation.” Out, August 24.

Saffin, Croix A. 2021. “Wounds of White Supremacy: Understanding the Epidemic of Violence against Black and Brown Trans Women/Femmes.” In A Field Guide to White Supremacy, ed. Kathleen Belew and Ramón A. Gutiérrez, 136-60. Oakland: University of California Press.

Tourmaline. 2017. “Tourmaline on Transgender Storytelling, David France, and the Netflix Marsha P. Johnson Documentary.” Teen Vogue, October 11.

Recommended Readings

Anderson, Tre’vell. 2023. We See Each Other: A Black, Trans Journey through TV and Film. New York: Andscape Books.

Ennis, Dawn. 2019. “Inside the Fight for Marsha P. Johnson’s Legacy.” The Advocate, July 23.

Fallon, Kevin. 2018. “‘Pose’ Isn’t Just Great TV. It’s Making Trans History.” Daily Beast, June 1.

Fischer, Mia. 2019. Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S. Security State. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Fischer, Mia. 2021. “Making Black Trans Lives Matter.” QED: A Journal in GLTBQ Worldmaking 8, no. 1 (February): 111-18.

Gossett, Reina, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton, eds. 2017. Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gross, Larry. 2001. “Coming Out and Coming Together” and “Stonewall and Beyond.” In Up from Invisibility: Lesbians, Gay Men, and the Media in America, 21-55. New York: Columbia University Press.

Additional Recommended Screenings

Disclosure. 2020. Directed by Sam Feder. Los Gatos, CA: Netflix, 100 minutes.

Free CeCe! 2016. Directed by Jacqueline Gares. New York: Jac Gares Media, 100 minutes.

Stonewall Uprising. 2011. Directed by David Heilbroner and Kate Davis. New York: First Run Features, 90 minutes.

United in Anger: A History of ACT UP. 2012. Directed by Jim Hubbard. Jim Hubbard Films, 93 minutes.

1 See the review of Happy Birthday, Marsha! by Blu Buchanan in this issue of Films for the Feminist Classroom.