A Body of Work - Labor Organizing in the Sex Industry: A Lesson Plan

“If you are selling your work, you’re selling the body that performs that work.”1

The blog post “Stripper with a Ph.D.,” subsequent podcast titled Stripcast: True Stories from a Stripper with a PhD, and interview shocked The Chronicle of Higher Education in 2014.2 Appearing under several pseudonyms, Dr. Outta Here/LuxATL/Claire discussed stripping during graduate school and career. She also told an inspired personal “quit lit” story regarding the untenability of academia, specifically describing male students drawing a ten foot penis on the whiteboard to intimidate her before class as one of her final academic last straws.3 Her experiences revealed one important aspect this lesson plan focuses on: the role of class. Dr. Outta Here/LuxATL/Claire realized that her worth within a broken system with limited opportunities for employment was not defined by her body or mind. The only way to survive and thrive under capitalism is to sell one’s labor for the most money.

Recently I was juggling six jobs: technical writing for two industries, teaching as an adjunct at three colleges, and serving as an editor in chief for a high school journalism project along with a seventh gig as a teaching assistant volunteer. That year I contracted a virus that held on for seven weeks. Like the workers in Live Nude Girls Unite!, I did not have sick days.4 I wrote a manifesto of my experiences, eventually published by Bitch Media, and fell into labor organizing as a lifetime career.5 The resulting involvement in activism opened my mind to the idea that having a body in the workplace is fraught with potential danger without legal union protections. All workers make money from their bodies and deserve equal respect.

Overview

The purpose of this classroom activity is to interrupt status quo perceptions about who sex workers could or might be and to critically ascertain futures of organizing nationwide under a heteropatriarchy. In framing the lesson, I draw from black feminist thought, specifically regarding the role of solidarity and action as required components to activism. Black feminist thought teaches that without energy devoted to change for all, full liberation cannot occur. Audre Lorde in Sister Outsider describes the erotic as a form of passion and women’s untapped sources of primordial energy.6 Pleasure Activism by adrienne maree brown is birthed from Lorde’s vision and demonstrates how doing work that brings us joy to repossess our bifurcated selves from domination and subjugation by a white capitalist heteropatriarchy is essential to maintaining the happiness of ourselves and those who are most marginalized.7 In her view, the goal of organizing justice is to have good lives, feel good, and be happy. Within brown’s collection, Chanelle Gallant argues that discussions on the morality of sex work fail to acknowledge that sex workers deserve fair working conditions. Ideals regarding the Protestant work ethic highlight our own inner biases on sex work. Gallant states, “People obsess about how sex workers feel about sex—not how they feel about work.”8 Giving pleasure is work, and unless we have unlimited means, capitalism controls the lives of all workers. All work tolls on the body. Initially reviewed in Films for the Feminist Classroom by Frann Michel, Live Nude Girls Unite! is an important film to revisit due to its solid coverage of a union campaign that failed to break under pressure. Twenty years later, precarity and just-in-time roles have only increased, and this film offers a thorough analysis of both gendered and racial politics at play within union efforts, showing how collaboration and cooperation is key to lasting change.9

Time Needed

Live Nude Girls Unite!, directed by Julia Query and Vicky Funari, is about sex workers at the strip club, the Lusty Lady, who led a union organizing drive to improve their employment conditions. The run time of the film is seventy minutes. The lesson plan is structured for two ninety-minute sessions, but it can be adapted for different class lengths.

Activity

The aim of these initial activities is for students to begin defining their conception of work and interrogate their own value system by considering others’ viewpoints.

Writing Activity: What is work? Define “work” in your own words.

Students complete a five-minute freewriting activity in which they respond to these questions by putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard and write without stopping or worrying about any organizational or grammar/syntax issues.

Partner Activity: Students form groups of two and undertake a verbal “believer” and “doubter” game: the believer must suspend disbelief and accept what they are told while the doubter must be critical of any inconsistencies. One person in the pair summarizes their definition of work while their partner occupies each role for approximately two to three minutes and then the students switch roles. I wrap up the activity by making a list on the board of core beliefs and disbeliefs about work from each group.

Large Group Discussion Questions

Overview: I first invite students to discuss their thoughts in both large- and small-group open discussion. I suggest sitting together with students communally as the film is screening, stopping the film at each time marker to ask the question (see below), and provide students an opportunity to write down an answer. There will also be a place where students can write questions/comments down anonymously, which I answer before class ends. The students answer each discussion question, and we end with a large group discussion.

- Does this film change your belief about what a sex worker looks like? Did it surprise you that Julia is a lesbian and a stripper? (05:00)

- Are strippers workers? Does sex work qualify as work? Why or why not? (07:00)

- The Wagner Act of 1935 still prevents both domestic and agricultural workers from unionizing, and companies and businesses try to divide workers through racist actions, which the film shows in the example of not hiring black dancers to work during peak hours (31:00). Why do you think the club placed this limitation on the black women they hired? Additionally, why were these women not allowed to work in the private booths where dancers can earn more money? (11:00-13:00)

- Why do you think the Lusty Lady chose the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) to serve as their representative for a first contract? Why did the Lusty Lady workers choose to represent themselves at the bargaining table along with a negotiator? Why did Julia, Jane, Tara, Decadence, Naomi, Velvette, Elise, and Scott (support staff) all volunteer to serve on the bargaining committee? (17:00-19:00)

- What is the difference between a 1099T (temporary) and W2 (part-time) employee according to the film? (22:00; 29:00-30:00)

- What is the purpose of a work slowdown and a work stoppage (strike)? (33:00- 35:00)

- What do you think of the film’s central conflict between the protagonist and her mother about sex work? Who is right and who is wrong? Or are they both right and wrong? (43:00-45:00)

- What was the role of coalition building within this film? (33:00; 59:00-63:00)

- Why do you think some of the strippers at the Lusty Lady were also graduate students? Does that change your perception of what a sex worker is? Why or why not? (8:00; 52:00)

- Joyce’s and Query’s different perspectives are symbolic of the antagonism between second and third wave feminism. Joyce Wallace, a second wave feminist and Query’s mother, states, “It is much better to work with your mind than your body” (52:00). Query later explains, “If I hadn't been part of a union effort I wouldn’t have as much control over my working conditions. And it didn’t matter how aggressive, or Jewish, or smart, or witty, or how strong I was. Personality didn’t provide me with good working conditions; being part of a group organizing successful union effort did” (65:00). What does each quotation say about what each woman values?

Reflection Questions: Ask students to consider in small groups of two and three how these questions apply to what we have learned from the film about collective organizing.

- In 2003, management lowered wages and the workers struck and won, but the Lusty Lady closed as a business. Afterward, the strip club became a worker cooperative but closed in 2013. Does this invalidate the workers’ efforts to unionize? Why or why not?

- Could the unionization of sex workers happen in any other state besides California? Why or why not?10 (Discuss historical union membership in states such as California, New York, Hawaii, and Alaska versus Texas and North and South Carolina. The Instagram hashtag #NYCStripperStrike created in 2017 by a woman of color activist and worker, Gizelle Marie, is also a useful point of discussion.)

Closing Activity: For the last five minutes of class, students complete the closing activity independently.

Query is no longer a stripper and works as a therapist. Google the other workers within this film (Siobhan Brooks, Carol Lee, Lily Burana, Elisabeth Eaves, among others). What did you learn?

Conclusion/Implications

Despite approximately six years of teaching experience, and despite the education and the high level of maturity of my students, when I taught this film at a college with a social-justice themed mission I found myself surprised by students’ perspectives. They stated that strippers and sex workers “asked for it,” that “shaking your ass isn’t a real job,” and “I could do that work if I wanted to.” I responded with “Why?” or “How did you come to that thought?” This style of questioning, “answer, affirm, redirect,” is a standard of union organizing pedagogy. The instructor answers the question, confirms the student’s perspective, and redirects to the overall message and learning outcomes.

Homework

This assignment is the culmination of the lesson plan activities and allows students to apply imagination and creativity as transformative forces within the classroom and beyond. Working collectively to change systems is for the benefit of all, and students are invited to envision change beyond their own worldview.

Select one option for a creative response to the film. *I am open to suggestions!*

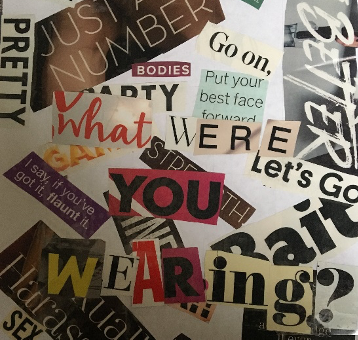

This collage is an example of a creative response through art.

Art: Create an artistic representation of your thoughts on the film; it can be drawn freehand (in color or black and white), painted, or performed. Include a 250-word description of how your creation reflects a theme or themes in the film.

Commentary: Write a 250-word review of the film for IMDB or Rotten Tomatoes to contribute to the online and public writing world.

Fiction: Write a 250-word literary piece from the point of view of one of the cast members, remembering to use imagistic language, well-chosen verbs, and precise nouns, to “show rather than tell,” and to avoid clichés.

Hashtags: Create original hashtags totaling 250 words about the film topics and themes (for example, #NYCStripperStrike is three words).

Gram It: Take a photograph representing your thoughts about the film style and content and post it to Instagram with an accompanying description of 250 words.

Interview: Contact activists and union members in the film and ask them questions about their roles in the film. Summarize the interview in 250 words.

Vlog: Produce a video blog of three to five minutes about your thoughts on the film and post it to YouTube. Compose 250 words describing how the vlog addresses a theme or themes in the film.

Film Terms and Definitions

Agency shop: A place of employment in which workers do not need to join the existing union, but nonunion workers must pay a fee to support the costs of collective bargaining.

Carrot over stick: A practice in which an employer expresses the intention to concede to workers’ demands during a campaign to organize a union but does not put these concessions in writing. Then, the employer can yank them away if union activity ends. Often this occurs when a union campaign begins revving up.

Last, best, and final: Last offer from the employer in a union contract campaign.

Maintenance of membership: A middle ground between “agency shop” and “open shop”; employees are not required to join a union, but they must meet with a union employee to discuss their rights.

Open shop: A workplace where workers are not required to join or support a union as a part of their employment.

1 Chanelle Gallant, “Fuck You, Pay Me: The Pleasures of Sex Work,” in Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, ed. adrienne marie brown (Chico: AK Press, 2019), 183.

2 Dr. OH, “Stripper with a Ph.D.,” Doctor Outta Here, September 13, 2012; Josh Boldt, “‘Stripping Was the Easiest and Quickest Solution,’” Chronicle of Higher Education Community, May 13, 2014.

3 Lux ATL, “Ten Foot Ejaculating Dick,” Stripcast: True Stories from a Stripper with a PhD, June 8, 2016, 19:26. See also Dr. OH, “Why I'm Leaving Academia,” Doctor Outta Here, July 26, 2012.

4 Live Nude Girls Unite! directed by Julia Query and Vicky Funari (New York: First Run Features, 2000), 70 minutes.

5 Veronica Popp, “For an Adjunct Professor, Academic Power Dynamics Feed into Rape Culture,” Bitch Media, February 11, 2016.

6 Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 53-59.

7 adrienne marie brown, “Introduction,” in her Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good (Chico: AK Press, 2019), 13.

8 Gallant, “Fuck You, Pay Me,” 178.

9 Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia, Gwendolyn Beetham, Cara E. Jones, and Sekile Nzinga-Johnson, “Women’s Studies and Contingency: Between Exploitation and Resistance,” Feminist Formations 27, no. 3 (2015): 81-113; Joe Berry, Reclaiming the Ivory Tower: Organizing Adjuncts to Change Higher Education (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2005). Con Job: Stories of Adjunct and Contingent Labor is a film and ebook available through the University of Utah Press; both are created by Megan Fulwiler and Jennifer Marlow with a release and publication date of 2014, and both can be accessed here: https://ccdigitalpress.org/conjob.

10 “Union Members—2019,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, January 20, 2020; Amber Ferguson, “NYC Strippers Strike: Dancers Say Nearly Naked 'Bottle Girls’ Are Grabbing Their Cash, Cite Racism,” Washington Post, November 3, 2017.