We Learn Together: A Conversation about Feminist Film Pedagogy with Frances Negrón-Muntaner and Elisabetta Diorio

A leading figure in various fields, Frances Negrón-Muntaner began making films as a child in Puerto Rico in the early 1970s. She defines herself as a “multimodal thinker,” who in addition to being a filmmaker is a writer, curator, visual artist, scholar, and activist. Her film work ranges from realist documentaries and experimental narratives such as AIDS in the Barrio (1989) and Brincando el charco: Portrait of a Puerto Rican (1994) to historical films such as War for Guam (2012) and personal meditations such as Paraíso (2020). Among her most significant media-related publications are Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture (2004, CHOICE Award winner) and the groundbreaking The Latino Media Gap (2014), one of the most comprehensive studies of Latinos in media currently available.1

In 2003, Columbia University recruited Negrón-Muntaner as a professor, an experience that initially proved challenging to sustaining her post-disciplinary practice. Six years later, Negrón-Muntaner founded the Media and Idea Lab to provide a different space for media praxis. An important part of what makes the lab unusual and transformative is its feminist approach to teaching filmmaking. Her feminist film pedagogy values collaborative problem solving, community building, and multiple forms of knowledge, standing in stark contrast to the university model, which is hierarchical, individualized, and grade-oriented.

In the lab, Negrón-Muntaner works with a broad range of collaborators, including professionals and undergraduate students. Whereas the current university model is founded on the premise that undergraduates are a tabula rasa, Negrón-Muntaner’s feminist film pedagogy presumes otherwise: that students do have knowledge and that the role of the teacher is not to simply transmit expertise but to provide the conditions for students to build on their knowledge and craft their own course of study. One position within the lab is the digital media assistantship, a long-term work-study position that involves collaboration with Negrón-Muntaner for the lab’s projects. As an undergraduate who has worked for three years in this role (2016-2020), Elisabetta Diorio experienced firsthand the impact of a unique, nonhierarchical approach to education. Here, she and Negrón-Muntaner explore the thinking behind the lab, why it matters, and how it might provide an alternative way forward for teachers and students.

Interview

ED: It’s funny—we have in common that we both applied to Columbia assuming we wouldn’t get in, and neither of us ever imagined we’d wind up here. And as a freshman in a new city, in a new and unfamiliar culture, surrounded by strangers and course options and libraries, I was overwhelmed by how much I did not know. Such a destabilization of one’s knowledge is not a bad thing, but I can’t emphasize how important it was to have a space that allowed me to do one thing I felt I knew how to do: video editing. This space gave me a feeling of knowing while in every other aspect I was experiencing a knowledge crisis. I’ve told you this before, but I really believe my work at the Media and Idea Lab is responsible for me staying in university and graduating this May. How were you able to preserve your values and your own way of working in this environment?

FNM: At times, it has been hard for me too. In contrast to many academics, I do not work to advance disciplines or to be promoted in a university hierarchy or profession. I do not even view my practice as a “career.” Instead, I see it as a way to disrupt coloniality, expand political possibilities, and foster everyone’s capacities. So, I had to determine how to both do my work and meet institutional requirements based on entirely different criteria and goals.

In the end, I persisted by elaborating and living four principles. One, know why you stay at the institution; that is, have clarity of purpose. Two, do not internalize the institution, much less collapse your identity with it. You may establish relationships in academia, but the main mission of all institutions is to reproduce themselves, not necessarily to nurture most of us. Three, create what a fellow filmmaker Louis Massiah has called, “a legitimizing community,” a supportive group of people with whom you are in meaningful dialogue. Lastly, if you don’t fit the mold, don’t try to; embrace the anomalous, which is how every transformative breakthrough happens in the world.

ED: Let’s talk about another beginning: how did you start in film?

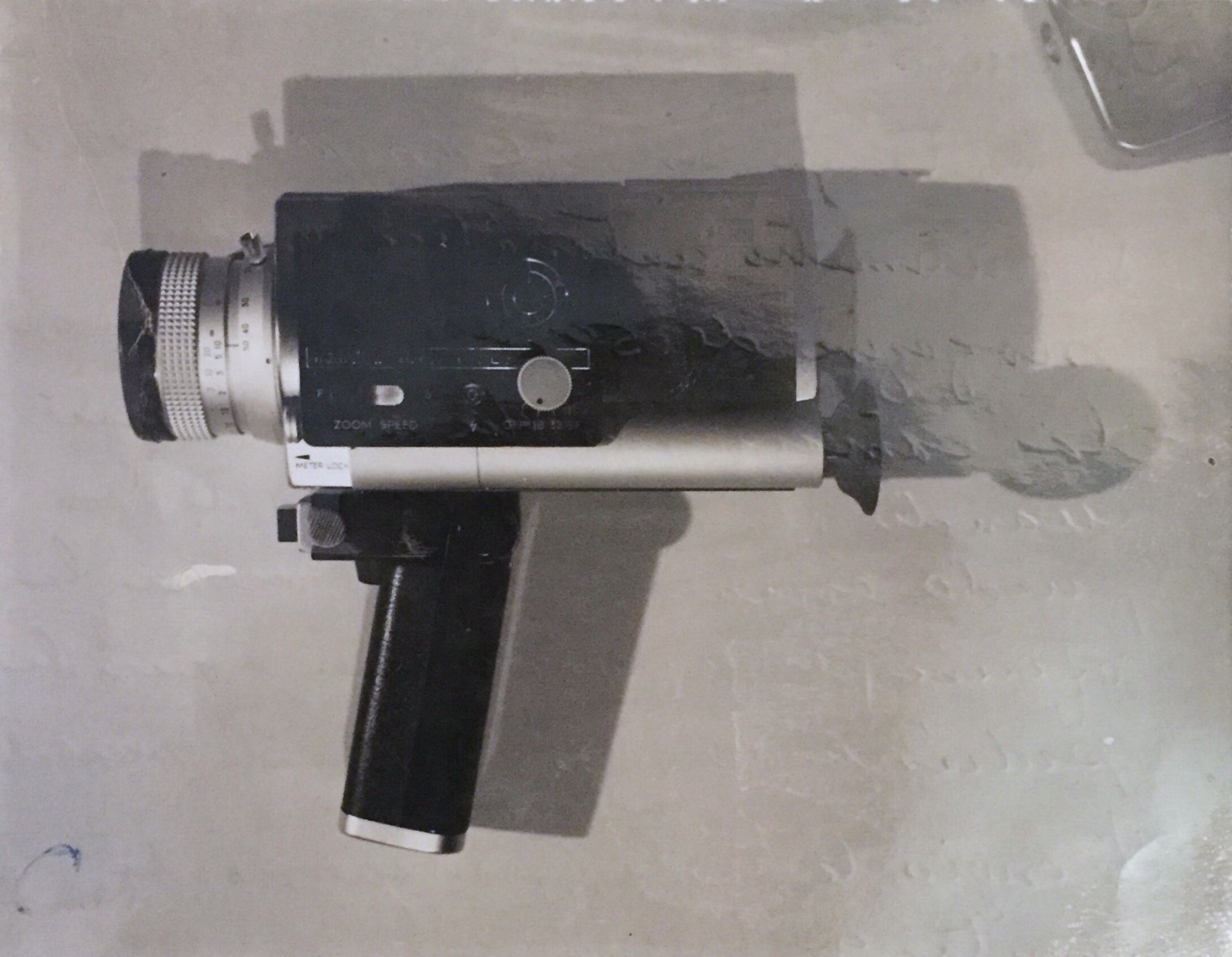

FNM: My initiation into film began with audio: at four, my grandfather, José Muntaner, gave me a Panasonic tape recorder and cassettes. My recordings included conversations, environmental sounds, and singing. A lot of singing! When I turned eight, I told my grandfather that I wanted to make a film. My grandfather, who was the director of the audiovisual department at the VA [Veterans Affairs] hospital told me that he had found a Super 8 camera at work and that I could use it “under his supervision.”

With  this camera in hand—and not much supervision—I started experimenting and made some short movies, mainly horror, sci-fi, and comedy; I also discovered a few tricks. One was how to disappear an actor from the set, like in I Dream of Jeannie and Lost in Space. Once I entered my teens, I stopped making films and became a photographer.

this camera in hand—and not much supervision—I started experimenting and made some short movies, mainly horror, sci-fi, and comedy; I also discovered a few tricks. One was how to disappear an actor from the set, like in I Dream of Jeannie and Lost in Space. Once I entered my teens, I stopped making films and became a photographer.

I found my way back to film after I migrated to Philadelphia. In retrospect, I believe that part of the reason is that migration was painful. I did not have any family in the United States, and my own never visited. I had to start from near scratch. During this time, watching and making films became a great refuge. It both connected me to home and allowed me to build new communities. As a Puerto Rican intellectual who had become part of a mostly working-class diaspora, I also saw film as an accessible medium to communicate with other Puerto Ricans in the United States. So, when in the mid-1980s someone close to my partner died of AIDS, I became part of the group that made AIDS in the Barrio. Our goal was to provide a platform for people to discuss how the epidemic was affecting us and how we could take care of each other.

ED: You released AIDS in the Barrio in 1989 and Brincando el charco in1994. Do you consider these films as part of a larger movement or shift in filmmaking? How do you feel the movement of filmmaking you were a part of has informed your beliefs about what filmmaking can be and how it can be taught?

FNM: Both  films represented firsts but in different ways. AIDS in the Barrio was the first Latino independent documentary to address AIDS, particularly its socioeconomic, gendered, and LGTBQ contexts. It was also the first in which a Latino religious figure, Father Floyd “Butch” Naters Gamarra, directly challenged the homophobia of the church, which we viewed as implicated in the deaths of so many. Formally, however, I would say that AIDS in the Barrio did not break new ground but followed the conventions of “ethnic realism.” Although I was critical of this aesthetic at the time, the four of us making the film thought that our core audience would find it more engaging than other options such as an experimental or reflexive film.

films represented firsts but in different ways. AIDS in the Barrio was the first Latino independent documentary to address AIDS, particularly its socioeconomic, gendered, and LGTBQ contexts. It was also the first in which a Latino religious figure, Father Floyd “Butch” Naters Gamarra, directly challenged the homophobia of the church, which we viewed as implicated in the deaths of so many. Formally, however, I would say that AIDS in the Barrio did not break new ground but followed the conventions of “ethnic realism.” Although I was critical of this aesthetic at the time, the four of us making the film thought that our core audience would find it more engaging than other options such as an experimental or reflexive film.

Brincando el charco was, among other things, a revolt against the ethnic realism of AIDS in the Barrio and the assumption of formal and political transparency. This response is related to how I experienced the release of AIDS in the Barrio in contradictory ways. On the one hand, it was transformative. I took the film everywhere to have conversations that I hoped would strengthen communities and save lives. On the other hand, I was placed in the position of “representing” the Puerto Rican diaspora. This raised many questions for me about hierarchy and power. I was light-skinned, born to middle-class parents, and a recent migrant. While I was a “sexile” (queer migrant) in the United States, I also had the privilege to access a graduate education.

Brincando el charco was, among other things, a revolt against the ethnic realism of AIDS in the Barrio and the assumption of formal and political transparency. This response is related to how I experienced the release of AIDS in the Barrio in contradictory ways. On the one hand, it was transformative. I took the film everywhere to have conversations that I hoped would strengthen communities and save lives. On the other hand, I was placed in the position of “representing” the Puerto Rican diaspora. This raised many questions for me about hierarchy and power. I was light-skinned, born to middle-class parents, and a recent migrant. While I was a “sexile” (queer migrant) in the United States, I also had the privilege to access a graduate education.

At another level, the film was part of a broader conversation. During the 1990s, there were significant debates around the concept of “representation” as diverse independent filmmakers were asking themselves whether telling their stories required alternative strategies. I thought the answer was yes, so Brincando el charco was a deliberate attempt not only to tell a different story but to tell it differently. In this process, I participated in a range of exchanges with other people of color, women, and LGTBQ filmmakers, mostly in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Europe. I would agree that all of this history made its way into how, what, and why I teach.

ED: How do you feel your beginnings affected your approach as a mentor to other filmmakers?

FNM: A lot, because, ironically, no one really taught me how to make films. My grandfather never sat with me to explain f-stops or lenses, so I learned by reading his books and watching him. The film school I attended in the 1990s offered effective film history and film criticism courses but failed to teach us fundamentals such as writing. Over an entire year, the screenwriting instructor did not discuss the craft or our ideas. As a result, I created Brincando el charco, my thesis film, mainly by trial and error and with the skills and love of some of my classmates and friends.

Fortunately, several years later, I helped to create the screenwriting lab program for the National Association of Latino Independent Producers (NALIP), an organization I cofounded in Los Angeles in 1999. The program aimed to mentor Latino independent filmmakers writing for film and television. I was part of the first class, and the experience was thoroughly formative as I both learned how to write screenplays and gained a legitimizing community. So, when I founded the media lab at Columbia, my model combined the “learning by doing together” method I adopted by necessity early on with a supportive environment that afforded each person access to the basic tools, mentorship, and a space to develop according to their interests.

ED: My high school film class was also a “lab” environment based on learning by doing: we would make film after film and correct mistakes from the last film in the next one. My film teacher also never lectured us but just provided us the space and the best equipment he could get. I would go after school and on weekends to the school to edit my films. One time he allowed me even to smuggle a desktop computer home in my car for the weekend when I was trying to finish color correction for a premiere. He also let me build an entire set in our school’s theater and showed up every day on his spring break to supervise the shoot. That lab environment was the only reason that by the time I came to you, I had editing skills and could tackle the storytelling challenges of the first film we completed, Innocence Nevermore (2017), featuring poet Tato Laviera. So, it seems we also both learned filmmaking in a hands-on, self-taught way, but what do you feel is different about beginning and learning as a filmmaker now versus when you were doing it?

FNM: There are many differences. Among the most obvious are technology and cost. Schools trained us in 16mm film and a Nagra reel-to-reel recorder. The equipment was heavy and altogether took about four people to carry. The magazines for the camera were only ten minutes long and about $100 without processing. Postproduction was long, intricate, and costly. It was out of reach for most people.

The fundraising process and sources were different as well. There were no crowdsourcing platforms, but there were many microfunds and allied organizations. For instance, if you look at Brincando el charco’s end credits, you will see the names of multiple small feminist and LGBTQ funds that no longer exist, alongside community organizations and bars. Given the themes of my work and how few Puerto Rican women were making films at the time, I experienced fundraising as a political practice that involved extensive coalition building.

Reception infrastructure has changed, too. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, there were no social media or streaming services. The main way to watch an independent film was by going to a film festival or indie theater, which usually played the film for a limited time. This process, like fundraising, required and created embodied communities, so although your audience would likely be smaller than today, the bonds ran deep.

ED: We’ve talked before about how you do not see film only as a means of self-expression or a formal exercise. What is your definition of film?

FNM: In a word I think cinema, similar to all arts, is research. As Pablo Picasso once claimed, “I never made a painting as a work of art; it’s all research.” In my view, the best cinema also does not merely document or “represent” but produces knowledge and furthers justice. This outcome is accomplished through what French practitioners often call “mise-en-scène” and “montage,” that is, how spatial relationships are arranged within a scene, and how editing links scenes together. Through montage, one chooses between actions, images, and perspectives; combines them; and lays bare the relationships between elements, bringing new possibilities into being.

ED: Is that why you created the Media and Idea Lab?

FNM: Yes, we could say that. The lab began when I realized that the only way I was going to make films in the academy was by integrating my multimodal practices and founding a place to work with others along these lines. Since the university did not offer financial support to create the lab, I reached out to students, faculty, and colleagues. I quickly learned that first-year students were particularly motivated to work in a different space than the classroom. In part, this was because they may have already been working this way in high school and were familiar with the tools and the craft of filmmaking from a very young age.

In the lab the concept is that students may learn from my experience producing and directing films over the past thirty years, but it’s not a class setting. It's a space to consider the problems that every film poses and their repercussions. By our own standards, we might fail, but that’s what it is about; to recall Samuel Beckett, “fail again, fail better.”

ED: The way you threw us into the work as if we were already editors conveyed a lot of trust. You also brainstormed aloud with me and were very honest about the problems you didn’t yet know how to solve. These practices gave us a lot of independence, a lot of equality, and a lot of responsibility, and I think that encouraged us to rise to the occasion.

Learning in an environment where the student is assumed to be a knower stood in complete contrast to my other university courses. I’ve been in photography courses where the professor comes in, looks at everyone’s photographs for three hours, and is the only arbiter of which are good. No one else is able to give any feedback, so we all sit there silently for the whole semester. By the end of the course, no one really knows each other very well. And no one knows how to speak about someone else’s work, how to articulate what appeals to them in a photo, or how to make a photo for an audience other than the professor. How would you describe the difference between the lab and a traditional university course?

FNM: In my view, the prevalent paradigm in higher education is still authoritarian and disciplinary. I propose a model where collaboration, question- and problem-centered challenges, and participation are at the fore. And this begins with the course outline itself. For years, I have started my classes by inviting students to suggest revisions to the proposed syllabus so we are all invested in the class. Each course also includes multiples ways of learning or what I refer to as the six “Cs”: critical thinking, or engaging critically with ideas and practices presented in various forms; creativity, or the ability to relate and make connections between similar and different concepts, contexts, and forms; connectivity, or the practice of learning from others in multiple settings; communication, or the capacity to tell stories, share information, and express thought through diverse means; and curiosity, or the ability to craft questions that prompt further learning and queries.

This is how I organize Video as Inquiry, the course that lab participants sometimes take. In this class, there are no exams, quizzes, or papers. The only assignments are capacity-building exercises and a project that can be pursued individually or in a group. It also encompasses three different layers: conceptual, historical, and production. That is, students discuss theoretical frameworks used to analyze cinema; become familiar with film traditions that place knowledge production at the center such as documentary, ethnographic, and experimental; and acquire technical and writing skills to make independent work. Lastly, the course includes a unit on listening that we all curate and various work-in-progress sessions to comment on each other’s films.

ED: The pedagogy that you've employed in both Video as Inquiry and the Media and Idea Lab can be described as a “feminist pedagogy.” For you, what are the components of feminist pedagogy?

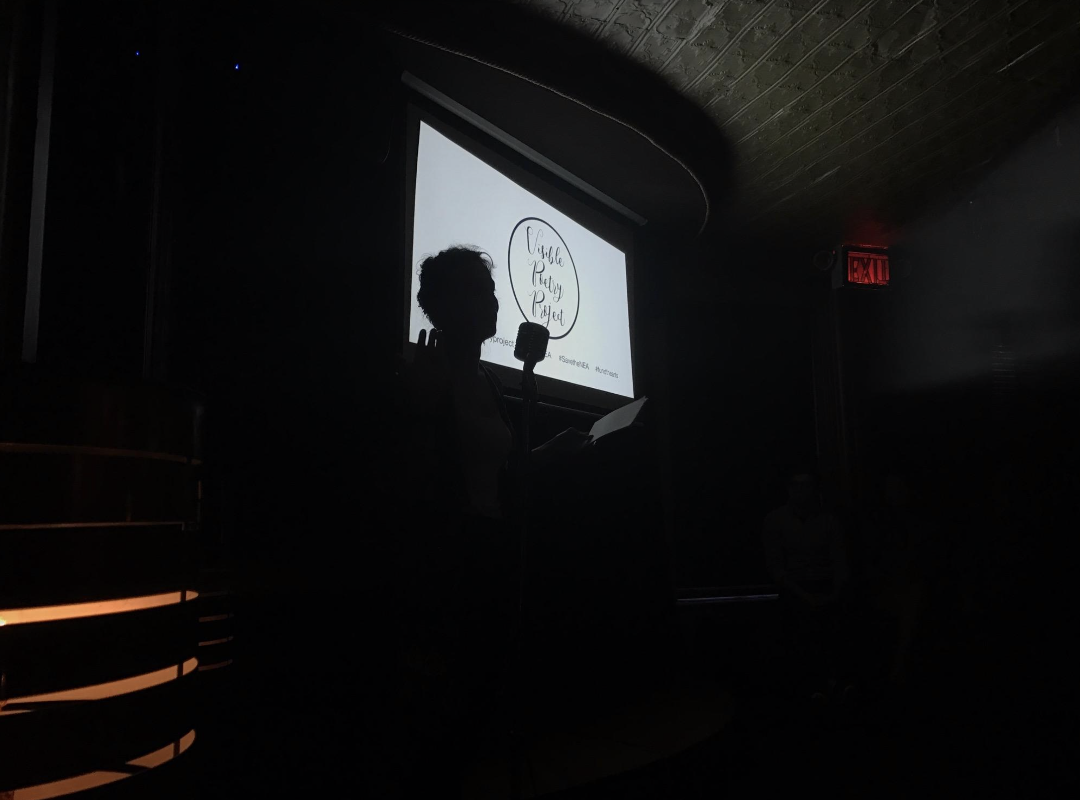

FNM: For me, feminist pedagogy, as other pedagogical traditions with similar aims, entails a collaborative, participatory, and transformative approach to knowledge production. I learned early on that it was particularly difficult to make a film without a community. However, community building is not simply a practical necessity; it is a core goal of the process, as art practice suffers without exchange. For instance, I hired Michelle Cheripka, a student at Columbia, in 2012. She was the first student who worked in the lab for several years. She graduated in 2016 and cofounded the Visible Poetry Project shortly after. In 2017, she asked if I could submit Innocence Nevermore for this project, but I had not completed it since she left the lab. I asked you [Elisabetta] to take a look, and you finished it quickly. This was, of course, great for the film and the lab. But with that project another important thing happened: I continued working with Michelle and linked Michelle to you.

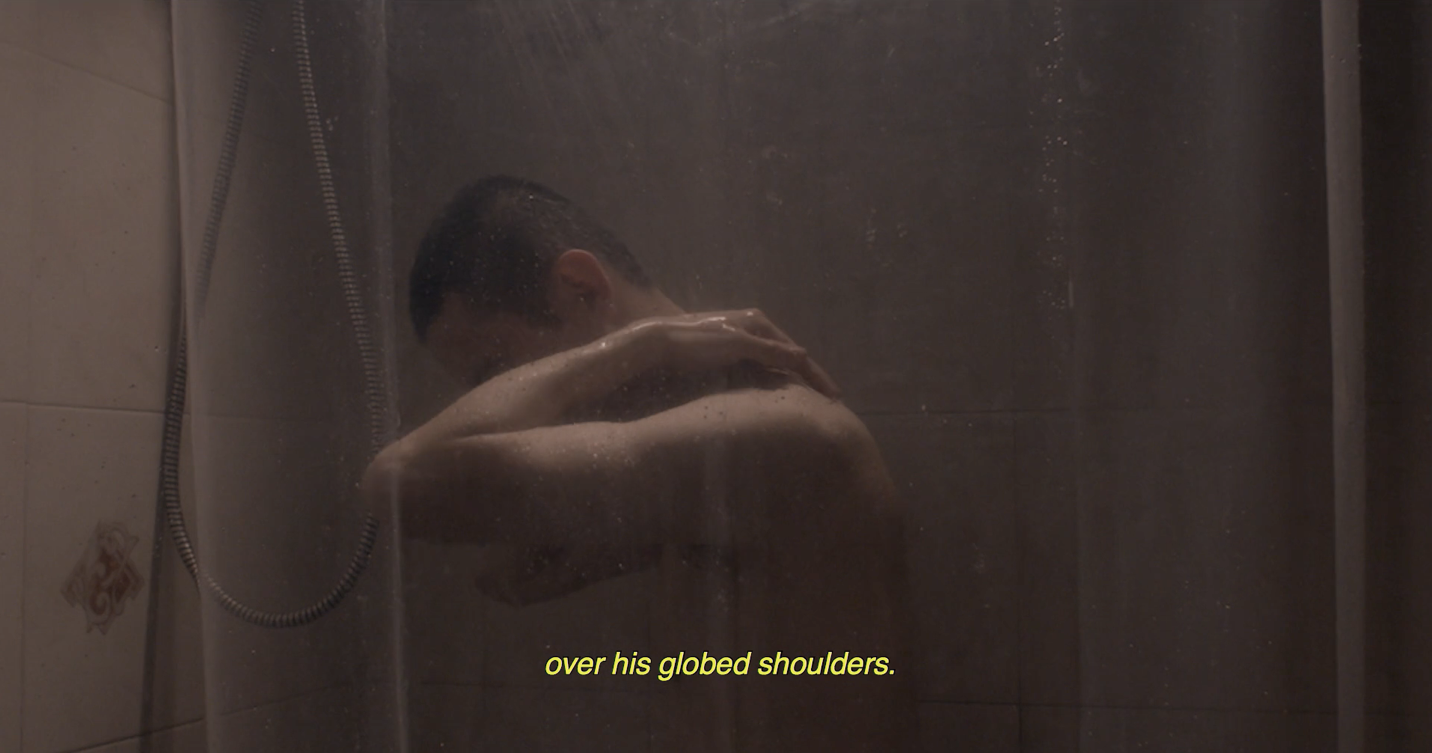

ED: A  year after we completed Innocence Nevermore, Michelle reached out to me to edit her short film Threshold for her 2018 contribution to the Visible Poetry Project. And then, in 2019, I directed my own film, The Sailor Melts, which connected me with a community of poets and filmmakers in New York City and overseas. So, that initial connection opened up this three-year-long collaboration for me and became something in its own right. And now, with your new project, Valor y Cambio, I’ve gotten to know other film producers in the city and Puerto Rico who are also at the start of their film careers, and we are all bonded together by these projects that we believe in.

year after we completed Innocence Nevermore, Michelle reached out to me to edit her short film Threshold for her 2018 contribution to the Visible Poetry Project. And then, in 2019, I directed my own film, The Sailor Melts, which connected me with a community of poets and filmmakers in New York City and overseas. So, that initial connection opened up this three-year-long collaboration for me and became something in its own right. And now, with your new project, Valor y Cambio, I’ve gotten to know other film producers in the city and Puerto Rico who are also at the start of their film careers, and we are all bonded together by these projects that we believe in.

FNM: Yes, this is the complexity of change: it often arises from pain. In this case, a process that began when one professor wanted to continue her film practice in a place where she had no community ended up creating multiple communal possibilities that will hopefully become richer and denser over time.

ED: Certainly there are many women who choose to work in hierarchical and patriarchal ways, but mostly I find it to be a very different experience to work with other women, both in this lab and on crews for my own films. Filmmaking with female colleagues enables a really strong level of trust, support, perseverance, flexibility, and helpfulness, and I don’t feel as much pressure to prove my competence or “professionalism.” You were the first woman I worked with who was an established filmmaker. I think when you see a woman who is more experienced in exactly the kind of work you want to do, who demonstrates effective ways of navigating these challenges, and who is the kind of leader you want to be, it is a wonderful thing. It feels like there is a possibility for you to emulate that. Sometimes it doesn’t feel possible if the leader is a man, because if you tried to do everything exactly like he did, it would still be perceived differently.

Additionally, the films we were exposed to both in Video as Inquiry and our work on various projects introduced me to a much broader spectrum of filmmakers and really got me outside of a very male, white, and American-centric film tradition. After my first year at college, I went back to my favorite DVD store in Austin and, for the first time, I noticed there were many names missing from their “great directors” shelves. At the same time, I don’t think either of us would say it’s always been easy. I’m curious, what are some challenges or frustrations with this way of working?

FNM: In more than one way, making films within an academic setting is not always “efficient.” I have missed many deadlines! Professors and students have to deal with classwork, exams, conferences, service projects, summer and winter breaks, and other interruptions or obligations. This rhythm is sometimes hard to explain to other collaborators working in NGOs or independent media companies, who generally have a top-down model and need to consistently “deliver” for supervisors, investors, and funders. In addition, not all students thrive in the lab environment, and when you encounter a student who does, they are in the university for just a few years. Finally, time and resources are limited, so we don’t always have the necessary skills or materials to solve a problem or solve it quickly.

The university is considerably less diverse than my own media community. For instance, some of my projects include languages other than English (mainly Spanish) and emerge from histories that are not generally familiar to many in the United States. These circumstances have presented challenges, as working on these projects requires not only cinematic knowledge but also other forms of knowledge: linguistic, cultural, historical. In other words, while the lab is a feminist and decolonial space, it is still embedded in the university. But the fact that it exists allows for new possibilities, including the joy of making films in a certain way.

ED: Yes, it is very intimidating to have to develop the skills as you go and not be totally prepared for everything. The challenges weren’t just technical. I’m not sure if I’ve ever told you this, but for the first year of working with you, I thought I was going to be fired every time we had a meeting. At the beginning, I was so afraid of making mistakes, of creating something you would dislike. I also remember you telling me that Michelle would say no when she couldn’t do something, and that was an important part of working together. I realized that it never occurred to me to say no to something, which I think can be a challenge for some young women who are really intent on pleasing everybody. So, the lab taught more than filmmaking. It gave me a more mature attitude toward mistakes by showing me how wrong directions can be useful in bringing a film to completion. It also encouraged me to develop my own sense of agency as a filmmaker and collaborator. I learned that I do have a distinct voice and vision that I can contribute to our work, even if at times it would have been easier to give up that responsibility by simply following directions.

In this particular pedagogical method, you learn by failing over and over again, and, through that failure, becoming more fearless and more trusting of yourself. It can be a challenging way of learning because, while it allows for a lot of missteps, it doesn’t coddle you or hold your hand. Do you feel the Media and Idea Lab model can be applied more broadly in university settings and the media industry or that it will always be something separate?

FNM: I do, although it will involve major transformations. Presently, Hollywood produces about six hundred movies a year to generate profits and ensure the reproduction of power relations that favor the industry. To this end, the industry is organized hierarchically, develops stories based on stereotypes, and is led by a few decision makers, who are mainly white and male. Same for the university: many institutions sustain dominant thinking and view their mission as training people to fit the job market or exploit it. So, spaces like the Media and Idea Lab are not only countermodels but also part of broader movements to bring new worlds into existence and shift away from colonial epistemologies and economies of profit, competition, and extraction.

ED: What you say makes me think of my spring 2018 internship at a big production studio whose unpaid interns were mostly grabbing coffee, filling in spreadsheets, taking out the trash, and staying out of the way in the name of “working their way up.” But many people work like that for years without pay and without advancement. And the space was very impersonal. Each worker treated the worker below them harshly and was treated harshly by the person above them in return. The hierarchical power structure defeated the purpose of working in the arts for me in the first place, which has always been about community, collaboration, and shared goals. Not only was the work environment less than desirable but it seemed like a complete contradiction to what the Media and Idea Lab stands for—promoting a more just society, strengthening community, generating new knowledge. That internship pushed me to think about how I want to work with film and for what ends. As I was asking these questions, I would leave that job and come to work with you, and together we would explore how best to communicate ideas and narratives that I really stood behind and for which I felt a sense of urgency to get to an audience. It occurred to me then, I choose this way! I'm interested in how the lab has shaped you as well. How do you think you have changed during seven plus years of this lab experience? How has it affected you as a filmmaker, educator, and/or person?

FNM: I am more convinced than ever that change is urgent and imminent. The reality is that many faculty and students want to escape the university and that the university is failing us at multiple levels. I may not have survived, nor made some of my most relevant work, without the lab. Out of the lab came my studies on media such as The Latino Media Gap and films that preserved the contributions of key cultural figures such as Tato Laviera in Innocence Nevermore. Equally important, the lab has supported young professionals and students, who I believe are producing critical knowledge and will continue to do so. Ultimately, similar to many scholars of color in predominantly Eurocentric environments, I felt my work did not “belong.” The lab made this question irrelevant.

ED: What is next for the lab?

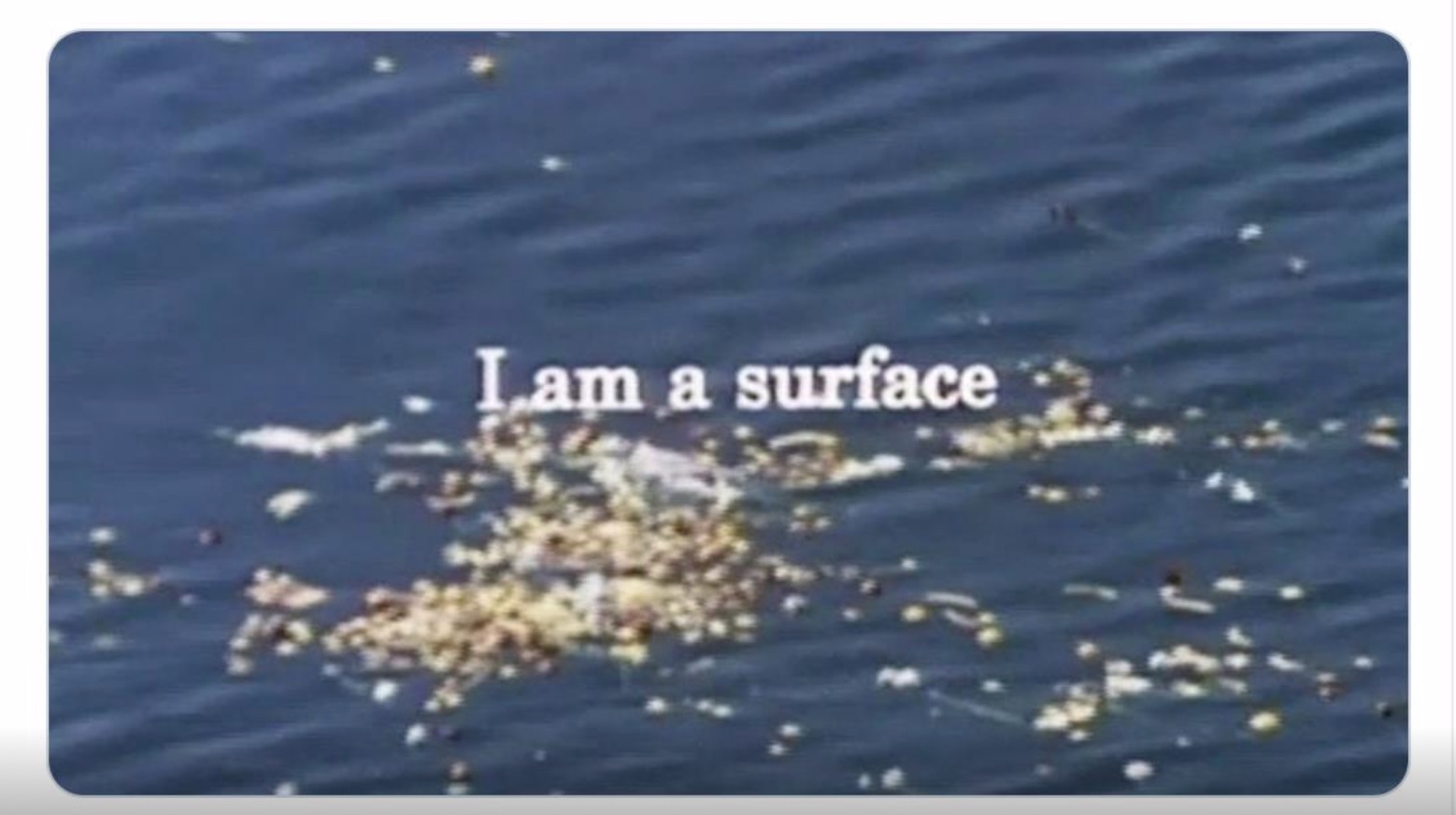

FNM:  You can still catch Days With(in), this year’s student-run showcase of the Video as Inquiry class responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. I am also finishing several films currently in post-production, including our project Paraiso, as well as Valor y Cambio, The Movie edited by Victoria Guillem, which marks a return to the type of political meditation present in Brincando el charco. Starting in August, the lab will release three media studies concerning race and recognition, Latinos and the comedy genre, and Asian Americans in media. Later this year, I will be starting a workshop that considers the challenge of visualizing what cannot be “seen” as part of completing a new film.

You can still catch Days With(in), this year’s student-run showcase of the Video as Inquiry class responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. I am also finishing several films currently in post-production, including our project Paraiso, as well as Valor y Cambio, The Movie edited by Victoria Guillem, which marks a return to the type of political meditation present in Brincando el charco. Starting in August, the lab will release three media studies concerning race and recognition, Latinos and the comedy genre, and Asian Americans in media. Later this year, I will be starting a workshop that considers the challenge of visualizing what cannot be “seen” as part of completing a new film.

ED: I too am really looking forward to finishing Paraiso. Because we started talking about the project during my freshman year and are returning to it my senior year, it’s neat how the film has actually made us think of evolutions and changes that have occurred during our time together. Seeing my old edits for the project is like reading old writing, and it makes me reflect on how your approach in the Media and Idea Lab has really allowed for growth and how it is one I'd like to pass down.

1 Frances Negrón-Muntaner, Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture (New York: NYU Press, 2004).

I want to talk about beginnings. I arrived in New York City from Austin, Texas, when I was eighteen years old. I came from a big public arts school and a strong community of creative young people, and I had made a lot of short films throughout high school. Choosing to attend a traditional four-year university as opposed to an arts academy, I was concerned I would have to put filmmaking on the back burner. And this is what happened until by complete chance I found a position at the Media and Idea Lab. I needed a work-study opportunity and it could have been anything. I could have been swiping student IDs or archiving books, but, instead, was able to create and grow at Columbia in a way I don’t think I could have found anywhere else. How did you arrive in New York City?

I want to talk about beginnings. I arrived in New York City from Austin, Texas, when I was eighteen years old. I came from a big public arts school and a strong community of creative young people, and I had made a lot of short films throughout high school. Choosing to attend a traditional four-year university as opposed to an arts academy, I was concerned I would have to put filmmaking on the back burner. And this is what happened until by complete chance I found a position at the Media and Idea Lab. I needed a work-study opportunity and it could have been anything. I could have been swiping student IDs or archiving books, but, instead, was able to create and grow at Columbia in a way I don’t think I could have found anywhere else. How did you arrive in New York City?