Unfinishing Histories in and through Film: An Interview with Artist, Writer, and Educator Mariam Ghani

Agatha Beins: Welcome, Mariam. Thanks so much for joining us today.

Before beginning, I want to give the briefest of introductions. Mariam Ghani, you are many things, some of which include artist, writer, and filmmaker. Your work explores how social, political, and cultural structures manifest and become material through a range of forms, media, and provocations. And your art exhibitions and conversations have spanned the globe—and I think the universe (we just don’t know it yet). And you’ve brought together a range of interlocutors and engaged audiences in museums, galleries, universities, and public spaces.

I’m beyond delighted that we have the chance to chat this morning. As I’ve learned more about your work, my appreciation for the way that you illuminate, explore, and critique ideology has only grown. And I’m especially inspired by the way that your work goes beyond critique to ask us to think about how we can perceive and imagine the world around us differently.

This conversation was sparked by What We Left Unfinished, which is your 2019 film, which I’m excited is available to stream on-demand, and educational institutions can purchase it for their campuses.1 I’m always happy when we can give creatives a shout-out in that respect. I’ve also learned about your newer film project Dis-Ease, which you describe on your website as a creative documentary exploring the impact of the metaphors we use to describe illness. And so, even though What We Left Unfinished, which explores Afghan film histories and constructions of nation-state, appears quite different from Dis-Ease, it seems that both of them are asking us to think about how dominant narratives take shape and form and how they impact us. So I hope that you will feel welcome to discuss both to whatever extent you find useful through our conversation.

I would love to start off by asking if you would mind putting in your own words your vision for What We Left Unfinished and Dis-Ease.

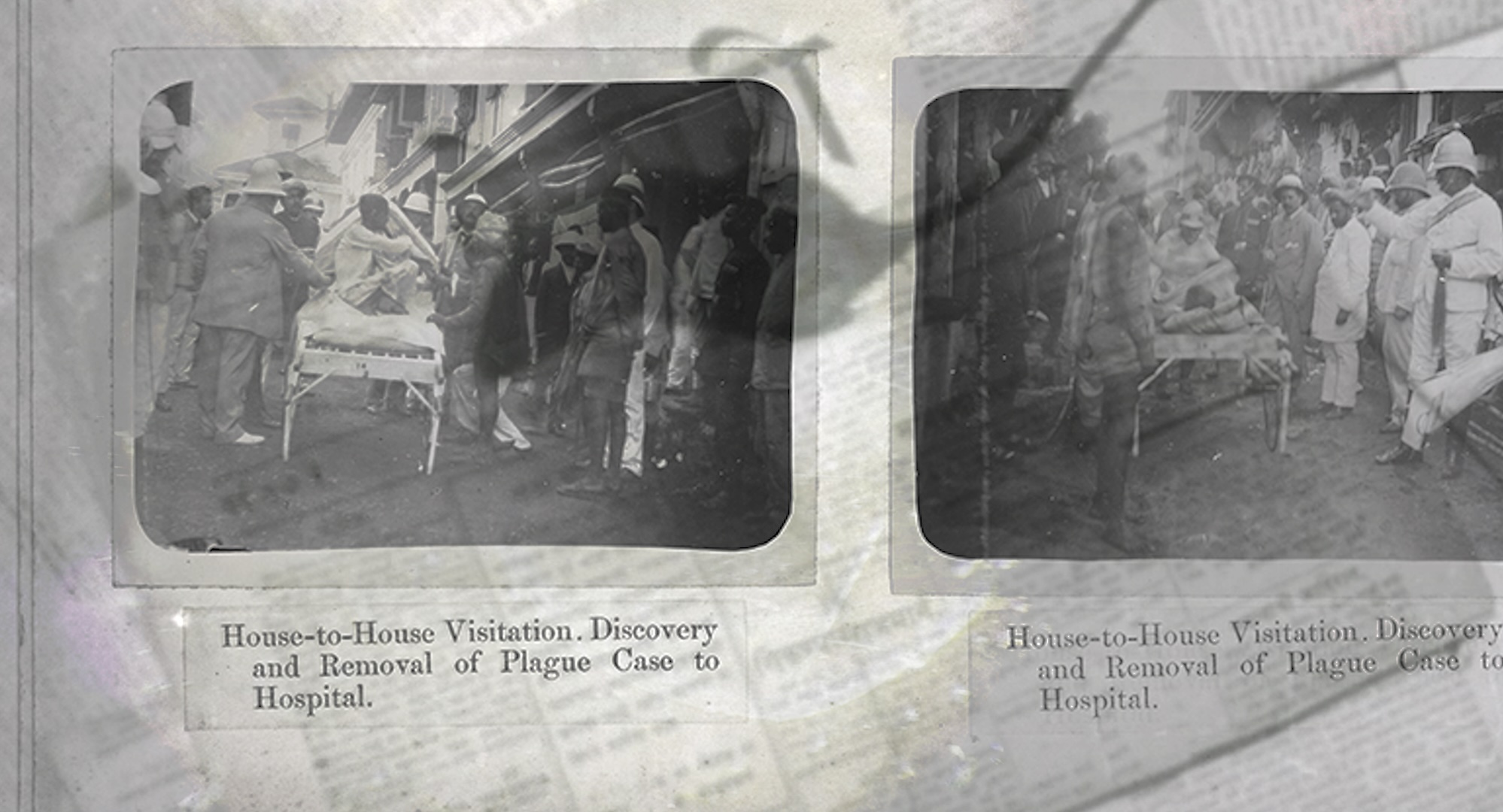

And Dis-Ease is a documentary about how we imagine disease and about the stories that we tell about illness, both in fiction and nonfiction media, since they affect what we do when we encounter illness, doctors, treatments, outbreaks, disability, sick people in our everyday life. And it really is like What We Left Unfinished, which is a story about how film shapes national imaginaries and becomes a kind of storehouse for national imaginaries that could have been but weren’t. Dis-Ease is also, in a way, a film about film—films have the power to shape real events and how we respond to real events. It is in part about outbreak narratives and their power to shape how we think about outbreaks and respond to outbreaks in reality. But it’s not just about outbreak narratives. It covers a wide range of media about disease.

Agatha: It’s so interesting to think about how film might be a way to bring in these multimedia narratives as well. It’s also really exciting this direction that you’re going in, regarding Dis-Ease’s topic and the collaborations that you’ve experienced in making it.

Mariam: It’s been a long process making Dis-Ease. I started working on it in 2017, so it’s shaped by my experience of the pandemic. It was a very different film before COVID-19. I’d actually almost finished a full cut before the pandemic started and then I had to throw it out and start over—not so much because I had changed my thinking but because it was a different world into which the film would emerge. It was a world in which the debates and the discourses that I was tapping into for the film had become much more widely discussed and had surfaced much more into mainstream media. And so the whole approach of the film had to change.

I think this kind of filmmaking, which is a bit essayistic and is based on very deep dives into archives. It has a kind of database element to it where you could make five or seven different films out of the material. It’s not a narrative-driven filmmaking process, and so there’s always many different possible paths through the material and many different ways in which the film could be constructed. That’s part of the fun, and also part of the massive challenge of making films like these, especially with Dis-Ease. What We Left Unfinished in a way was a slightly simpler film to make because it’s really drawing only from one archive. And from a legal perspective, let’s say, just in terms of licensing, it was a lot simpler, with only a few sources to license from. But with Dis-Ease, there’s almost ninety different archives that we were working with for the film. So it was a very complicated film to finish.

Agatha: I think you’ve alluded to this question already, but I’m wondering if you have thoughts about how your more current film projects build on or might move in different directions in relation to your previous work.

Mariam: I think, like most artists and filmmakers, I’m always trying to build on previous work and grow my practice and take on bigger challenges and make more complex works. I’m always trying to explore new ideas and take on new areas of research, just for my own interest. I don’t want to keep making the same work over and over again or keep going back to the same well of research.

With Dis-Ease, it was different. It was initially a commission from the Wellcome Trust. They came to me in 2017 because they were doing this multi-city project called “Contagious Cities” that was organized around the centenary of the 1918 flu pandemic. They had artists in residence in five different cities, and they asked me to be the New York artist in residence. They gave me a very broad brief. They just said, “We need you to make something about contagion, and it would be good if it’s also about cities and virality and migration.” And I was like, “Okay, sure.” Because I’d never made anything about public health or disease, I started with what I actually know, which is language. I went to the Susan Sontag essay “Illness as Metaphor,” which was a long-time favorite of mine.2 That’s where I started the research for the project. I made a short film that was much more closely linked to the Sontag essay.

I had also put together a mini think tank of graduate students at CUNY. Seven graduate students from different disciplines worked with me to research this film for Wellcome, and we had gathered so much material. We put together this massive Zotero database. And I felt like, “Oh, well, this is a feature. There’s so much more material than I can fit into an eight-minute short. I want to keep developing this.” So then I started pitching it as a feature, but the road of this feature has been a very long and rocky one—partly because of the pandemic, and partly because it’s a strange film to pitch and fund. You know, it’s not an obvious film to make.

Agatha: It seems harder to develop one of those one-sentence tag lines that really encompasses the complexity of what you’re trying to do. Which I love, but it presents challenges.

Mariam: Yeah, sometimes it presents a challenge to make a film about ideas.

Agatha: So, moving on to thinking more specifically about film and what it can do as a medium, I noticed one of the phrases that’s included in the trailer for What We Left Behind. It describes this film as a testament to the power of film, and I started meditating on this and what idea it conveys. It took me in two directions. One is about the way the Afghan government understood film to have a power in conveying certain ideas about the nation-state or about the government, and it recognized that losing control of film and its representations also presented a threat. And then, thinking about your work, there is a lot of power in the kind of documentary filmmaking that you and others do to open up questions about these politics of representation, how we remember and narrate the past, and how we situate ourselves in relation to those narratives. So I was wondering if you have thoughts about the power of film to reflect and create meaning as an aesthetic form. And then, if you’d like to talk about how you try to achieve that in either of the film projects, I would love to learn your ideas.

Mariam: Yes, film does have this power to create meaning. I think what is really essential always, for me, is to think about how the form in itself carries meaning. When working with archival material, there are a lot of specific considerations that come into play. Archival material carries its own history, its own material history, its own formal charges, and has all of its own concerns embedded in it, which you then have to reckon with.

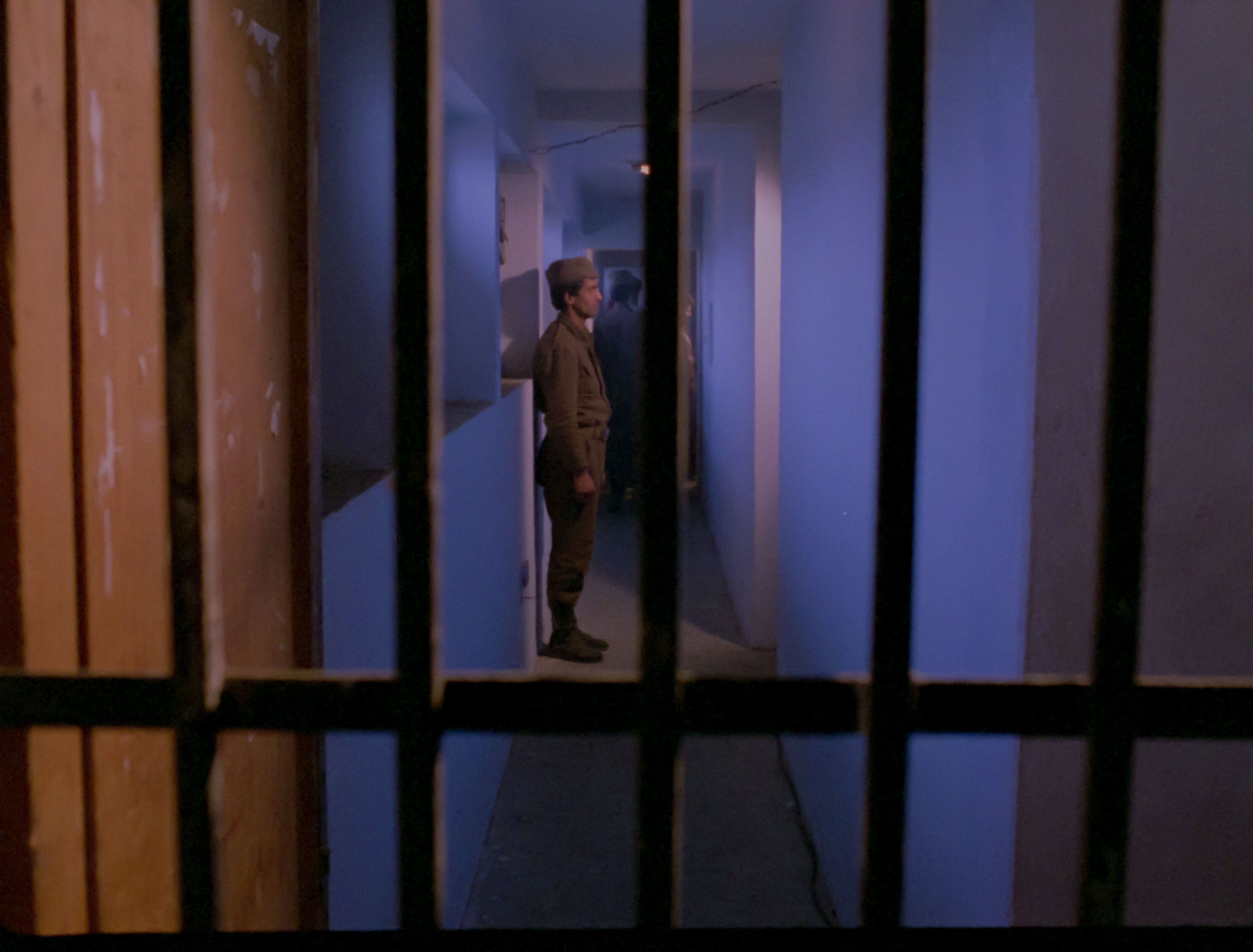

I think with What We Left Unfinished, in the construction of that film we were trying to work with what we called a “productive friction” between image and sound, specifically between image and text. We found these uncanny resonances between the footage from the unfinished fiction films and the words that were taken from voiceovers that were excerpted from interviews with the filmmakers.

I think a good example of that is when Wali Latifi is describing the assassination of President Mohammad Daoud Khan and his family and finding them all slumped over their meal at the dining table in the Gul Khana Palace. What you’re seeing on screen is a fictional scene from the film Almase Siah (The black diamond) by Abdul Khalek Halil where there’s this family—all were poisoned—slumped over their meal at a dining table. And then it cuts to the actual room in the Gul Khana Palace where Daoud’s family was actually found, with a very brief shot of that actual table. Then you see me in a red head scarf walking through the room. The present-day footage is never labeled, is never identified in the film, so only people who recognize these places will access that extra level of meaning. I did omit that information deliberately. But that scene is an example of this uncanny resonance between fictional footage and a historical event, and, of course, there’s no footage of this historical event. But it’s one of these images that seems to resurface again and again in films in the years that follow it. That was why we wanted to use this fictional scene to represent it, because it felt like this historical event emerging from the collective unconscious in a completely unrelated film.

Agatha: I appreciate your work to try to get the kind of multi-layeredness of this period in Afghanistan’s history. It might be a little bit of a cliché, but the palimpsest comes to mind as this kind of layering of narratives. I know that in other interviews you talked about the ethics of representation when working with archives, and so I am grateful for your thoughts about that as well—how you represent those folks who you interviewed. In a way, I think it recognizes that we all are kind of caught within a sociopolitical moment, which both opens up opportunities but also constrains our agency in certain ways.

I’m so interested in your discussion of the uncanny, as well. For me that brought up the way that film allows certain modes of juxtaposition that can make uncanniness visible cognitively and also in a very sensual, sensuous way. We feel it through film in a way that might not be conveyed in other media. There’s also the power of the unstated, which, to me almost has more power because it can reflect those collective agreements, those collective social narratives that are just so ubiquitous, we don’t say them anymore. So we stop seeing them and recognizing the way they shape us and our thinking. I don’t know if any of those themes might resonate in Dis-Ease, or if you wanted to offer any preliminary thoughts about the way that you’re trying to use film as a medium to tell a story about disease.

Mariam: The palimpsest is really relevant, in a way, to Dis-Ease. One of the things that I’m doing with archival material and Dis-Ease is literally layering things. In Dis-Ease I’m working a lot more with archival material that I am very directly in disagreement with—trying to subvert in some way, or trying to use the material against itself in various ways. So I’d say, in Dis-Ease, because of the breadth of archival material drawn from a lot of different sources, we’re using it in a wider variety of ways than we do in What We Left Unfinished. There are sections of the film where it’s almost straight documentary, so this material is being used to support the analysis that the expert interviewed is giving. Then there are sections where it’s being used as the best evidence of the critique that a speaker is advancing. Basically, you show the footage and it critiques itself. It’s like, you show the footage and it basically critiques itself. There’s a lot of WHO [World Health Organization] footage and global health footage that works that way. It’s sad but true.

Agatha: You mean literally like what you might see through a microscope?

Agatha: To me, that brings up interesting questions about scale and how that’s another juxtaposition that you seem to be engaging.

Mariam: Scale was a really big thing in the construction of this film. It actually has a scalar structure.

Agatha: Can you say more about that?

Mariam: It’s not something that I think is easy to pick up on, but it is what we think of as the secret structure of the film. It starts microscopic, and then it gets bigger and bigger and bigger. The entire film really is not only about how we imagine disease, but about how scientific ways of seeing the world create those kinds of imaginaries. So the circle of the microscope is a really important recurring image in the film. It’s what marks all the chapter titles.

Agatha: I can’t help but think as well about the kind of vision centrism that we have grown up with and the way in which seeing really becomes affirmative of truth and reality. So I can see a lot of ways to play with that and capitalize on that.

Mariam: It’s true. One of the interesting things about creating Dis-Ease involved working with a lot of 16mm film that either doesn’t have sound or has only optical sound, and so I didn’t get to do sound design for the film until quite late in the process—actually just this past January [2024]. It made such an enormous difference to the film to add the layer of sound design and then to mix the sound. We did a spatial mix and really thought a lot about where to place sound in space and how small or large sound should be, depending on scale. Reflecting the trajectory of the visual scale, sound starts really close and narrowly focused, and then it gets bigger and bigger as the film goes on. And there’s a lot of scientific ways of hearing in the film. There are underwater microphones, and there are some medical recordings of the body, anechoic recordings, things like that.

Agatha: Wow. What a full-bodied experience, which seems appropriate for thinking about something that permeates the boundaries of our skin.

Mariam: That’s the idea. I hope it does come across and work in the way we wanted. It made a huge difference for me, moving from the cut before sound design to the cut after sound design. It feels much more visceral and embodied as a film.

Agatha: I can’t wait to experience it. I’m sure you also can’t wait either.

Mariam: It’s going to premiere in August 2024 at the Tate Modern. I think that’s the earliest it will happen.

Agatha: I’m also hoping to use some of our time together to think about pedagogy. First, I wanted to amplify the resources that you offer on the website for What We Left Unfinished. There’s a wealth of discussion questions and prompts that I think would be relevant to so many different kinds of classes, such as those in film studies and archival methods and research, but also in history and political science. You mentioned area studies as well. I teach in women’s and gender studies, and I can see a lot of these questions being useful. For teachers who might want to screen What We Left Unfinished, and if you want to think ahead to Dis-Ease, what would you want them to keep in mind when doing so?

Mariam: I really wanted to think about this when putting What We Left Unfinished into educational distribution.3 I think it’s so useful when a film goes into educational distribution to produce discussion guides and suggest films and readings to have it be part of a larger curriculum. It always really helps me as a teacher to have those kinds of guides and suggestions.

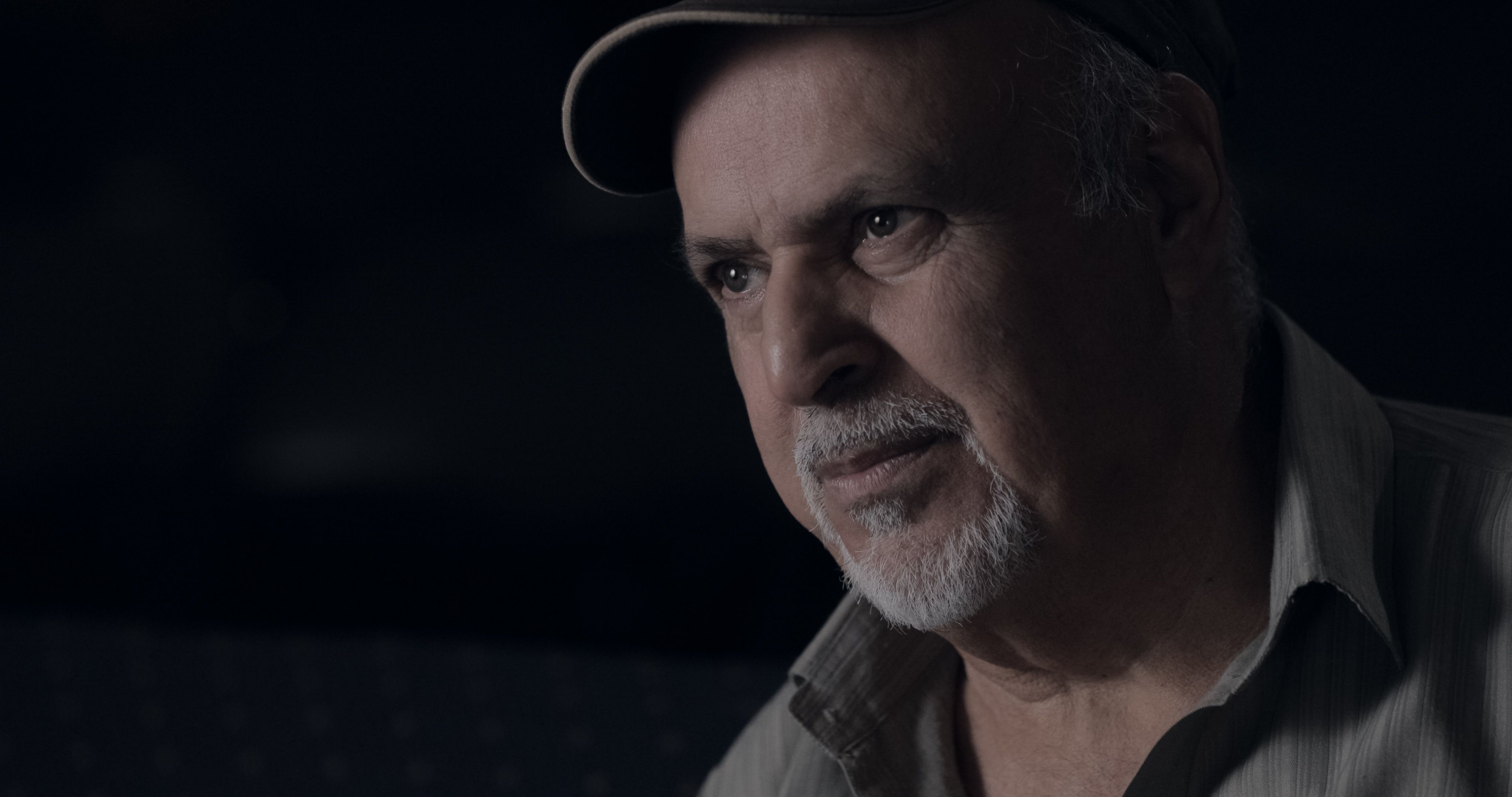

Teaching this film really depends on what kind of classroom you’re bringing it into and what you want to use it for. When I was making What We Left Unfinished, there were a few different audiences that I was imagining, and I was always thinking about it going into educational distribution because there’s a real dearth of films about Afghanistan to teach with. There’s very little about Afghan cinema, of course, and very few Afghan films in general that you can find easily to teach. So it was something that I always imagined being a kind of gateway drug to other kinds of Afghan cinema, and maybe Central Asian cinema in general. So, yeah, I always thought it could be used in area studies. Once I had screened the film at festivals I realized it was really appealing to film studies people, to this kind of cinephilic audience. These people really loved the film when it was on its festival run. So then I made a discussion guide tailored to that kind of audience as well.

One reason I was interested in making this film relates to questions I had that were really, in a way, universal questions about the choices you make as an artist in these difficult times, in times of political repression, of censorship, of war. These are perennial questions that come back again and again in many different times and places, and I think are questions that can frame the film in almost any classroom.

It speaks to the very different experience, obviously, that women had during that period, even though they experienced relative freedom in the cities—but just in the cities under communist control. Nowhere else; just in those cities. And they still faced embedded biases against the profession of acting and being viewed as a “loose woman” for being an actress. It’s also the difference in being a visible part of filmmaking, being this face on the screen versus being behind the camera and having that protection of being invisible to the public.

Both Yasamin and the other actor, Said Miran Farhad, that I interviewed for the film, had very different experiences from the directors. They both talk about having been physically threatened by opponents of the regime and having been in really dangerous situations. And Yasamin later had really, really terrible experiences under the Taliban because she stayed in Afghanistan, unlike the directors who had access to more privilege. She stayed. She’s from a village north of Mazar-i-Sharif. She went back to her village and started a secret school for girls because she’d originally been trained as an educator. She ran it for quite a while, and then the Taliban came after her, and they beat her really severely. She ended up having a miscarriage. Then she started her school again because that’s how she is.

Agatha: That’s striking. She sounds like a powerful figure, and I am glad that there’s at least one woman who gets to be represented.

Mariam: I tried to interview more women, but she was the only one who was willing to talk to me at that time. Because she was already on a Taliban death list, she kind of didn’t care. Most of the women active in film during that period, who were still in Afghanistan and still active in film, didn’t want to be interviewed.

Agatha: Which says something else about the silences and the gaps in the way that history and the present moment is narrated.

Mariam: And I’ll say also, when I took the film back to Afghanistan and I showed it to everyone, I asked if there’s anything they wanted me to take out. Yasamin was really unsure about the very end of the film when she says, “This will just lead to another Taliban. If we keep not paying attention to culture it’ll just be the same thing all over again,” which was very prescient. Her whole political analysis in the film is extremely sharp, actually, but she was very hesitant about that line. At first, she wanted me to take it out, and I agreed to take it out, and then she changed her mind and said, “Leave it in.” And she did have to flee the country, ultimately.

Agatha: I appreciate having more texture to that part of the film. Without it, I’m sure I wouldn’t have realized the significance of those few seconds.

Some of the things that came up in your comments, which I was thinking about also when preparing for this interview, is well, first, I know nothing about Afghan cinema—or really much about Afghan culture—which is, I think, both a product of US imperialism, but also just my own lack of self-education. So I’m glad to be learning it now. But I think what you were saying about this film being a gateway to realizing there are really rich cultural artifacts and aspects of places that we might not think of as hubs for these kinds of cultural productions is important and useful. And hopefully, with the digitization projects, access will become a little easier.

Mariam: What’s unfortunate there is that although the digitization project actually did get quite far—they digitized about two-thirds of the films—nobody got the hard drives out. And there wasn’t an off-site backup.

Agatha: That just attests to the importance of your film.

Agatha: Those are some really complicated politics going on.

Mariam: That was depressing. I have some scans of films because I had been working on restorations pro bono with a couple of friends of mine. We had actually restored three full films, which Criterion was supposed to stream, but the deal with the filmmakers somehow fell apart, and I don’t know how.

Agatha: This also, I think, brings up the way that film as a form and medium carries some of these complexities with it that other artistic products might not. Not that it’s exceptional, I’m sure there’s a lot of overlap in some ways.

I know we have only about ten minutes left, and I want to be mindful of your time. I have one more question that asks you to think and reflect on pedagogy. I know that you are an educator. I know that you’ve worked in more formal settings in a classroom and workshops, but you also work with interns, and you mentor students and aspiring artists, which I think is another form of pedagogy. So, speaking from this experience, I was wondering if you could talk about how you think about using film and video media in your teaching, perhaps to think about as art and as a form of representation, as well as in the ways you teach students about the filmmaking process. I don’t know much about your experience, so I just wanted to open it up for you to take in any direction you’d like.

Mariam: Film and video are sort of at the core of most of my pedagogy. Most of my teaching has really centered around that. I have done some other kinds of teaching, but in my current job, it’s just “Film/Video Faculty” at Bennington College, because we have no rank and no tenure. So it really is completely centered around both the practice and the theory and history of film and video.

One of the ways we teach practice is by looking and watching and analyzing what has come before, what other people have made, how they’ve made it, breaking it down, looking at things frame by frame, shot by shot. We also look at many different kinds of productions and think about how they differ from each other or have commonalities.

One of the things that I teach at Bennington every fall is the senior capstone class. It’s for seniors who are doing advanced work, capstone projects, in film or video. One of the most fun parts is that I curate a screening series of one feature per week based on what the specific seniors in that class that fall are working on. I try to do really recent films, often things that I also haven’t seen yet. That’s always really great because you generally don’t get the chance to show features to undergrads when you’re trying to do an intro to video class. You have to show them a lot of shorter works and really spend a lot of time looking at things on a more micro level. Getting the chance to pull back and think about how features are constructed is a really fun change.

This past term I did a class based around the manifesto that Union Docs put out: the Beyond Story manifesto. It’s a manifesto that came out, I think, about three years ago, that was inspired by discussions in the documentary community around how much narrative there is in contemporary non-narrative film, like this impulse toward the narrativization of documentary—not just the push toward narrative, but the push toward mainstream narrative structures. You know, three act stories with strong characters. This is something that’s shaped by funders and financing bodies, but it’s also from audiences and film programmers. There was a pretty robust discussion for about a year around this manifesto and the question, “What are all the other ways in which non-narrative film can be organized and why is that important?” Because form also has a politics, right? The politics of that kind of story are very specific. Imposing that kind of story on material has an effect, one of which is to imply that the world makes a certain kind of sense that is linear and progressive, which is not actually how the world works for most people. It tells us that stories have individual protagonists, which is also not how the world works for most people.

Agatha: Yes, it echoes the kind of narratives that emerged out of the Western European Enlightenment tradition, which is important to think about. I appreciate your highlighting the politics. No story is neutral, right? I mean, all stories come from a perspective, but when we presume there’s only one approach, it sort of neutralizes it, almost as if it’s the natural way to tell a story.

Mariam: And that’s what the manifesto was drawing attention to: this is not actually a neutral form. This is a form that very much has a politics, and to pretend that it doesn’t is disingenuous. So I organized a class around that manifesto, and it was fun. We looked at very narrative-driven documentaries, and then ones that were working in completely different ways. Bennington is great because I do get to organize classes like that, apart from the normal studio sequence.

I think for me—I haven’t actually thought about this in a while—but the pedagogy of using films and videos in class I think has to do with getting students to really come to their own conclusions about what it is that they’re watching and giving them the space to do that before telling them anything. I mean, it’s all about just teaching them how to watch and how to understand what it is that they’re seeing. It’s a basic media literacy principle, right? It’s so important to give them those tools because this is what they swim in every day. They need this desperately in order to function in today’s world.

Agatha: Yes, it’s so important to recognize both that film has certain specificities in its form and what it does and the way we can use it as a tool, but also opening up these more universal questions and more universal literacies as you were saying. These questions about documentary narrative film are also relevant to watching a TikTok video or Instagram.

Mariam: And I think that’s what’s so great about seeing students become makers, going from being consumers to makers. This is why in every theory class I teach, I give the option of making something instead of writing a paper. Very often students who have never made a time-based piece before will try it out, and sometimes they come up with really fantastic things. Watching them go from consuming to making is always really exciting because that is a form of knowledge production and analysis. You see them make these leaps in understanding by taking the tools into their own hands.

Agatha: What a powerful observation and teaching experience to leave us with. Thank you so much, Mariam.

Endnotes

1 More information about What We Left Unfinished can be found at Ghani’s website.

2 Sontag, Susan. 1977. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

3 Educational resources for What We Left Unfinished can be accessed through the film’s website.